(click to enlarge)

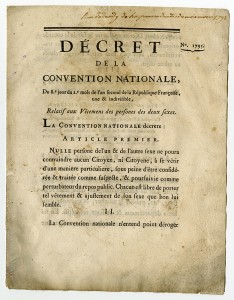

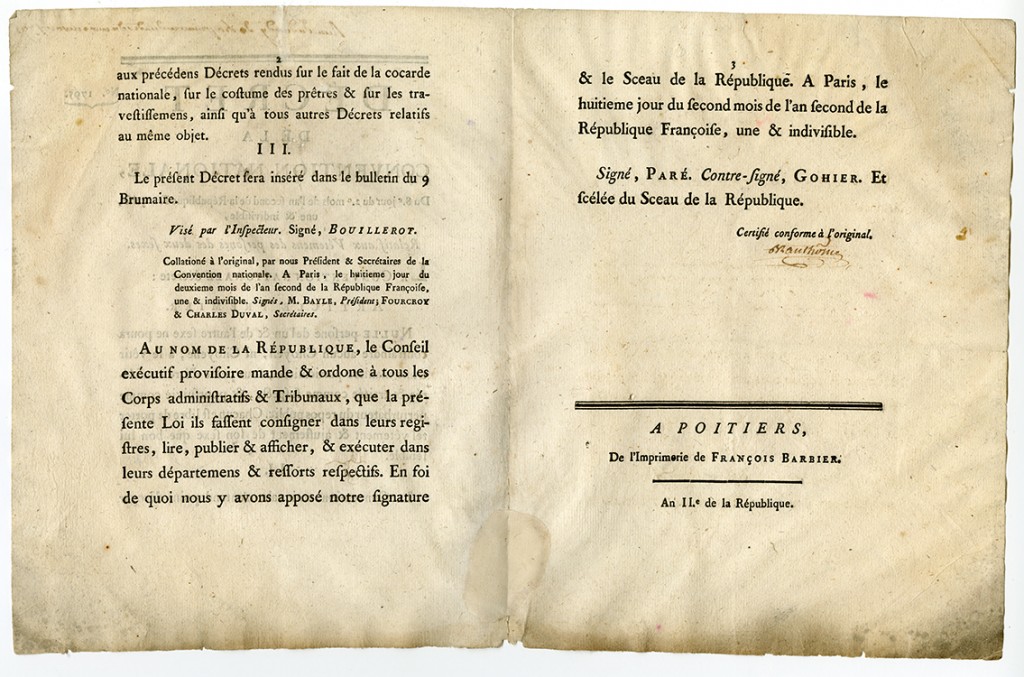

In early November 1793, amidst the most violent period of the French Revolution, the National Convention issued this decree declaring that the citizens of France were “free to wear such garments appropriate to their sex in the manner they see fit,” adding that individuals attempting to force another to dress in a specific manner would be subject to the penalty of law. The existence of this document—which we recently brought into the collection— begs the question: ‘how had the subject of clothing become such a divisive topic that legal remedy was deemed necessary in order to maintain public accord?’

Following the downfall of the monarchy, political factions gyrated and machinized at dizzying speeds, vying for power over a nation in chaos. In this highly charged atmosphere, political affiliations or sympathies were frequently conveyed sartorially. Even the verbiage used to describe certain coteries was based on clothing terminology; the segment of male commoners largely responsible for the storming of the Bastille was known as the sans-culottes, translating essentially to ‘without breeches,’ due to the fact they wore long, loose trousers rather than the skin-tight knee breeches associated with the aristocracy. By the Reign of Terror, a period in which more than 15,000 people met with the guillotine’s deadly kiss, fine garments traditionally associated with the elite, such as the elaborate robe á française or heavily embroidered and embellished habit á la française, were downright dangerous to wear, and many anecdotes of aristocrats borrowing clothing from their servants in order to obscure their identity are found in journals and memoirs of the era.

Color was highly symbolic during this period. At the start of the Revolution, France’s traditional colors of red and blue were combined with the Bourbon monarchy’s white to symbolize the union of ruler and ruled. This trifecta of colors was worn as a badge of revolutionary patriotism, most commonly in the form of red, white and blue ribbon cockades, the wearing of which, by 1793, had become an obligation for both men and women and even foreign visitors. The wearing of the cockade was such an incendiary topic that many incidents of violence were recorded pertaining to this newly-minted symbol of French liberty. Some men felt that women should not be allowed to wear the cockade, that its display insinuated equal political rights, while some women refused to wear the cockade until legislation granted them political agency.

Early in the Revolution, those with Royalist sympathies sometimes expressed their allegiance by wearing purple, black and white or by incorporating the fleur-de-lys motif—another emblem of the Bourbon monarchy—into their garb. However, by the time the decree at hand was issued, a gesture that brazen would have almost certainly cost one their head; the ruling Jacobin party, led by Robespierre, was on a vicious mission to rid the country of their political enemies.

Meanwhile, many felt that these quibbles and quarrels over dress would best be solved by the introduction of a ‘national costume’ and various interested parties, including the artist Jacques-Louis David and an organization called the People’s Republication Society of the Arts, made attempts to introduce their visions for a united, harmonious way to habillé. None of these were successful as a lasting, meaningful practice, and so the problem of what to wear to the Revolution remained a significant thorn in the sides governmental officials until the they attempted to render the matter legally mute with the issuance of Décret No. 1795.

The subject of dress and fashion during the Revolution is incredibly fascinating and complex, certainly not one that we could do remotely do justice to on Material Mode. If you would like to learn more we recommend you to the following books: Fashion in the French Revolution by Aileen Ribeiro, Queen of Fashion by Caroline Weber and the recently-published Fashion Victims by Kimberly Crisman-Campbell. All are truly superb.