Promptly at 3pm on December 18, 1941, members of the American fashion press gathered at the legendary Rainbow Room in New York City and patiently awaited their introduction to emergency mode.

A fundraiser to benefit the British Ambulance Corps, the event showcased the latest wartime fashions issued to accommodate, “the prospective new way of life which people in this country may be forced to enter sooner than they expect.” Down the runway came the “Ickes Bike Suit” named after Harold L. Ickes, the then-US Secretary of the Interior. In days leading up, Ickes had vociferously predicted gas shortages in light of the American’s entrance into the fray of WWII days earlier, making a boom in bike sales a distinct reality. The same runway showed designer Madame Pauline’s matching set of “blackout bag and mittens…made of pink felt and prepared with a luminous process by Stroblite Co. to stand out in the dark,” while a waterproofed wool one-piece “Siren Suit” by Mrs. MacDonald of Andrew of Luxembourg featured not only oversized pockets, but also “a broad brown pigskin belt with cigarettes, flashlight and a pocket knife.”

The American fashion industry’s snap to adapt to the exigencies of war in the matter of a few days was less expeditious than one may think. After all, French couturiers such as Marcel Dormoy, Robert Piguet and Elsa Schiaparelli—among others—had begun offering what I like to term ‘conflict couture’ two years earlier; in late 1939 French couture offerings included thick wool air raid suits with a proliferation of pockets, fur lined “shelter boots” with slip-resistant soles and suits and outwear trimmed with glow-in-the-dark buttons, all issued under the label of one’s favorite maison de couture.

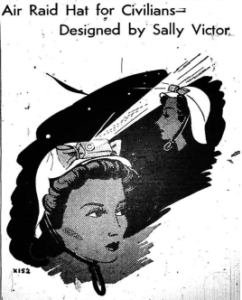

Never one to be left behind, American milliner Sally Victor’s air raid hats had been covered in Women’s Wear Daily two days before the 1941 fashion show benefit at the Rainbow Room. Victor, originally born in Scranton, PA had emerged as one of American fashion’s top milliners beginning in the early 1930s. She began her career working as a salesperson at the hat counter at Macy’s in New York City before moving on to become the millinery buyer at Bamburger’s department store in Newark, NJ. Following her marriage to Serge Victor, a ready-to-wear millinery manufacturer and the birth of her son, Sally gave up working for a time, until as the Boston Evening Transcript noted in 1933, “Every time she came down to his [her husband’s] factory however, she felt like doing something to those hats (with quick pinching gestures), and, when she couldn’t stand it any longer, she made him give up his designers and took over the job herself. She sees her four-year-old boy in the morning, telephones him during the day and sees him again at night, and feels he is much better off in the care of a nurse than a mother who just couldn’t stand giving up her work anyway.”

Victor’s talent and passion for the art of hat-making was repeatedly acknowledged by her industry peers. In 1933, Victor was one of the first designers tapped by Lord & Taylor for their ground-breaking promotion of American Designers, and subsequently Victor even had her own ‘pop-up shop’ in-store where her creations retailed for $9.75 (just under $200 adjusted for inflation today). The awards and accolades would continue to come Victor’s way in the ensuing decade; in 1943 she won the Fashion Critics Millinery award, not to mention winning Coty American Fashion Fashion Critics Awards in 1944 and 1956.

Victor’s designs of the 30s, 40s and 50s were some of the most frequently profiled by the American fashion press, right along with other top designers of the era such as Mr. John and Lilly Daché, who perhaps remain better known to us today. Victor’s quirky air raid hats, made a perfect fodder for Women’s Wear Daily, which described them as being made in a variety of materials “wether felt, straw or fabric has been fire-proofed in the firm’s workrooms. As a trimming, a small flashlight is posed at front, covered with flannel or some other durable and contrasting material, which lights easily by snapping the catch. The under-chin ties match the covering of the flashlight.” The author goes on to note the model in featured in the illustration above left is a white felt model with red red trim.

As Victor believed “style should never be sacrificed for service,” she would continue to create millinery looks with the wartime woman in mind. As fashion historian Nadine Stewart has noted in her wonderful MA thesis, Traffic Lights of Chic: American Millinery and American Style, 1937-1947, perhaps Victor’s “piece de resistance was a welder’s helmet covered in blue cloth with a red “V” for victory on the crown for the workers at General Electric. It was so successful General Electric featured it on the cover of its brochure for Arc Welding Supplies complemented with chartreuse leather work gloves. Victor apparently liked this design so much, that she later repeated it for her fashionable clients. The “Winnie the Welder” style appeared in blue and black felt in 1943.” Also this same year, a beret Victor designed for the “Army’s Cadet Nurse Corps made the cover of Harper’s Bazaar.”

The caprices of fashion are frequently reflections of the spirit of the times, during the 1940s this meant the anxieties stemming from a world engulfed in war were frequently made manifest in the fashions of the era. Today, I write this blog post from home as we are under a different kind of siege, the siege of disease. COVID19 has us hunkered at home shunning unnecessary human contact in an effort to fight an unseen enemy, one which has already reinvented the fashion landscape. This morning Native American activist and fashion designer Korina Emmerich, of the NY-based brand Emme, announced her line of fashion face masks using Native American motifs, which she has offered as part of her line for quite some time, to be sold out for the foreseeable future as she keeps up with an explosion in demand for examples that fall in line with consumer’s fashion sensibilities (not to mention her charitable endeavor to make and donate additional masks for each one sold).

COVID19 will undoubtedly reshape our world, but if history tells us anything, one question that remains is, ‘exactly how will it refashion your closet?’ World events, social and political change and new innovations in technology have long been driving forces in the evolution of fashion, and this moment is no exception.

2 responses to “Emergency Mode: The Wartime Hats of Sally Victor”

Well written and so informative. Thank you.

I would have worn these hats right now, nice content.