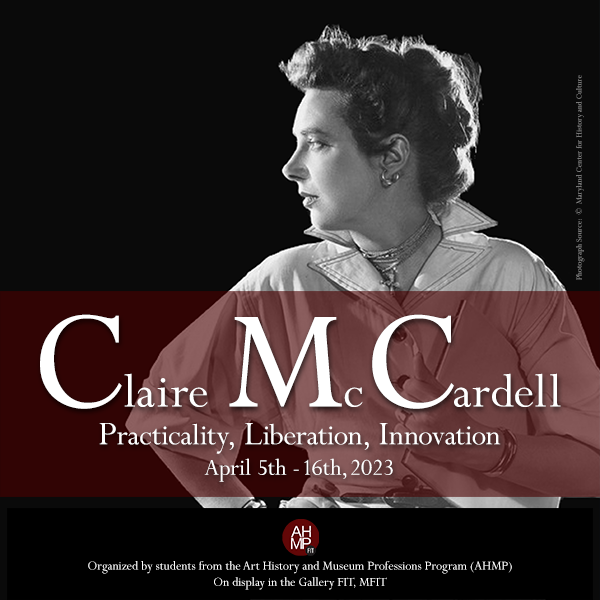

By Emma Sosebee, Monday, April 10, 2023

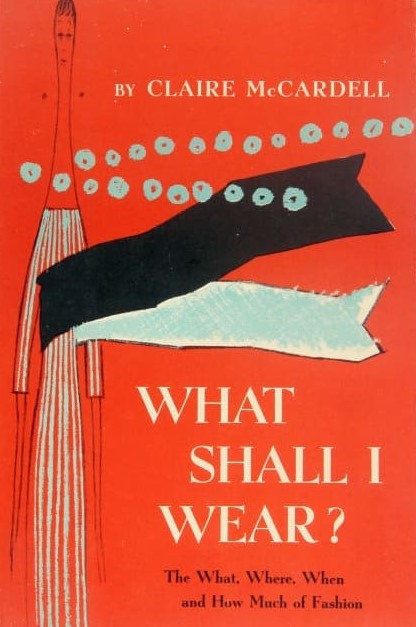

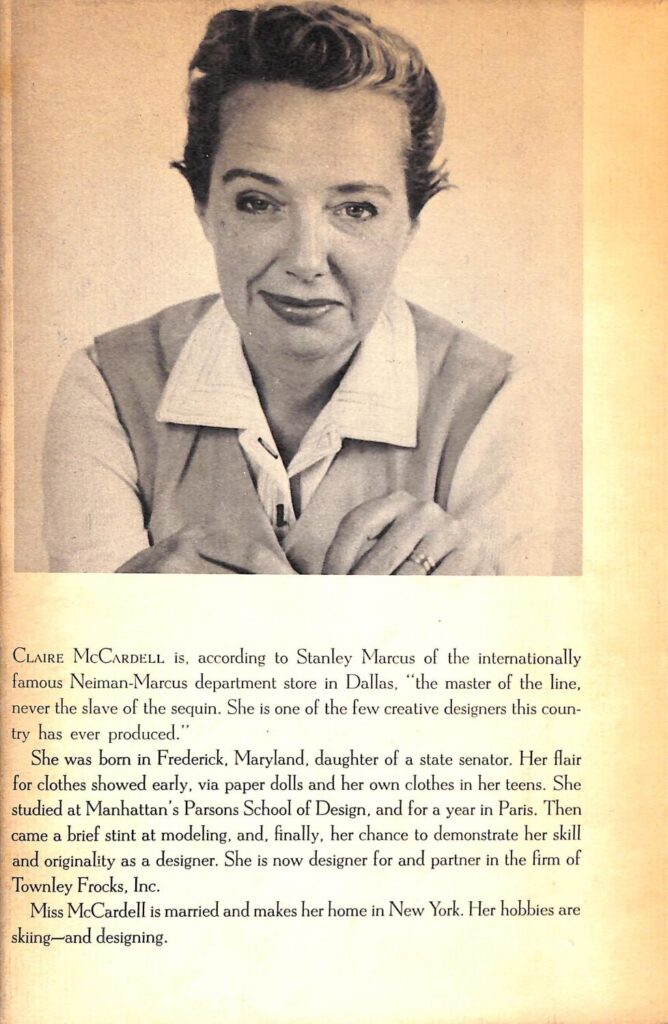

What Shall I Wear? The What, Where, When, and How Much of Fashion was the only book Claire McCardell wrote in her lifetime; just two years before her death, the book was originally published in 1956 by Simon and Schuster of New York. Accompanied by a variety of delightful illustrations created by Annabrita McCardell––whose specific relation to the designer is now unknown––the text is quite practical in essence. Witty and sincere, the book reads like a fashion advice column: from how to tie a scarf to suit one’s figure to sharing the importance of creating a signature look, McCardell used her professional insight to help American women in the 1950s dress with intention for any occasion. Though developing a sense of fashion may feel elusive due to the industry’s ever-changing trends, McCardell’s belief was that any woman could train her eyes to recognize good style and get her wardrobe in line; all it takes is a good teacher.

What is most interesting about What Shall I Wear is how much of the book remains appropriate for women’s lives (and, really, anyone interested in fashion) today, despite its 67-year-old status. As a product of an America quite different from the contemporary period, the book obviously has its moments of traditional 1950s thought––from glove etiquette to suggestions for appeasing one’s husband. Nevertheless, many of the designer’s ideas about fashion and how women should dress were relatively progressive for her time. In the first chapter, “What is Fashion,” McCardell addresses what I would argue was her most important philosophy: that clothes are for real people, and should therefore be designed in ways that are fully functional for the wearer. She adds that clothes are “made to be worn, to be lived in. Not to walk around on models with perfect figures.”

On a similar note, the designer also uses her introduction to remind her audience that there is no such thing as a “type” to fit into––if something in fashion does not feel right, there is no reason to force yourself into a certain style just because it is popular on the runway or the city streets. She recommended women wear the fabric or silhouette they feel best in, have fun, and play around. Fashion, though it can be intimidating to the average person, “isn’t meant to be taken too seriously.”

Instead of trying to confine women to a particular style––in which she very well could have used the book to only promote her latest collections––McCardell’s What Shall I Wear humbly served its readers by acting more as a general fashion guide. Better yet, it helped women of all ages to regain a sort of individual agency; to the American designer, understanding Fashion with a capital ‘F’ was not about conformity. A person’s chosen style should reflect their own imagination, thought, time, and energy. In other words, “The more yourself in your clothes, the better.” Evidently within her sportswear she stressed physical ease, but McCardell also hoped to impart the importance of “mental ease.” Above all, a woman should wear what makes her feel confident and comfortable.

With chapters on what clothes to pack for different trips, suggestions for mothers worried about their teenagers’ following certain trends, and even a helpful glossary of fashion-associated terms the designer labeled as ‘McCardellisms,’ What Shall I Wear was a necessity for 1950s women who were looking to both develop their personal taste and to understand the fashion world at large. The book’s reissue in 2022 with a foreword by contemporary fashion designer Tory Burch speaks to McCardell’s continued relevance within the industry.

About the Author

Emma Sosebee (she/her/hers) is a senior in the AHMP program and one of the curators of Claire McCardell: Practicality, Liberation, Innovation, on view at The Museum at FIT starting April 5th. Throughout her undergraduate career, Emma has developed an enthusiasm for how arts institutions care for their numerous objects. She hopes to pursue her interest in the collections management field upon graduation.

Further Reading

McCardell, Claire. What Shall I Wear? The What, Where, When, and How Much of Fashion. Abrams, 2022.

Martin, Richard Harrison. American Ingenuity: Sportswear, 1930s-1970s. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

Strassel, Annemarie. “Designing Women: Feminist Methodologies in American Fashion.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 41, no. 1/2 (2012): 35–59.