By Alexander Nagel, Thursday, May 19, 2022

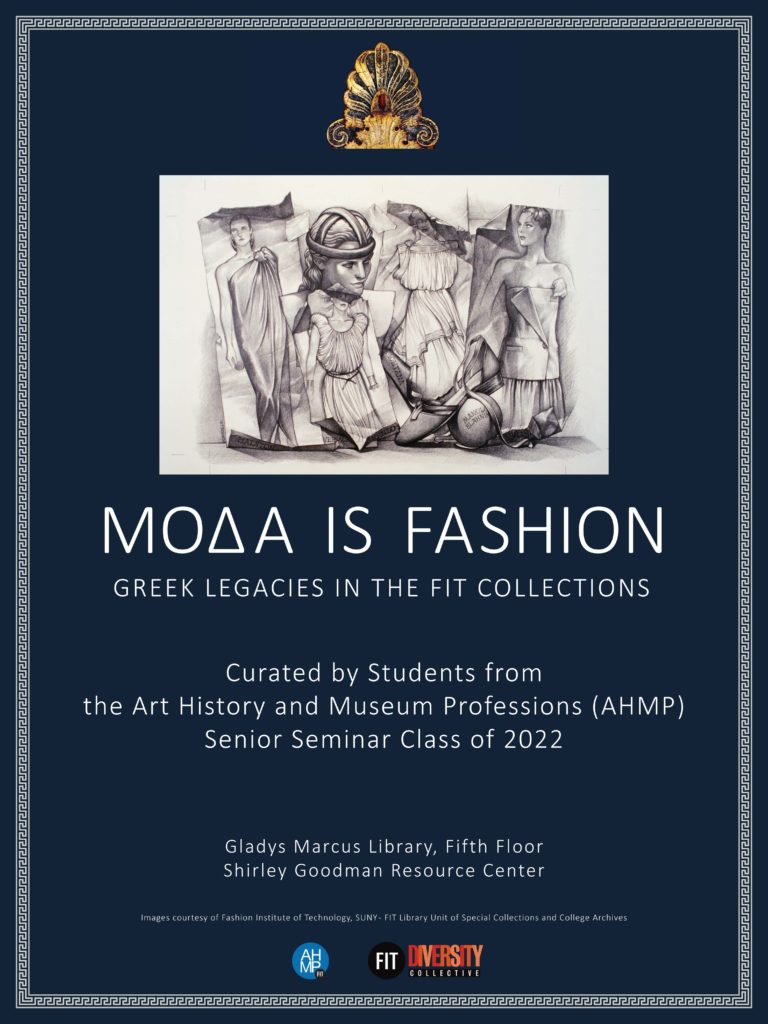

ΜΟΔΑ IS FASHION is the first entirely AHMP senior student class curated exhibition at the FIT Gladys Marcus Library on the State University of New York’s campus in downtown Manhattan. The Art History and Museum Professions program developed out of a Visual Arts Certificate program in the early 2000s. Today, many AHMP alumni are successful curators, archivists, educators, and writers.

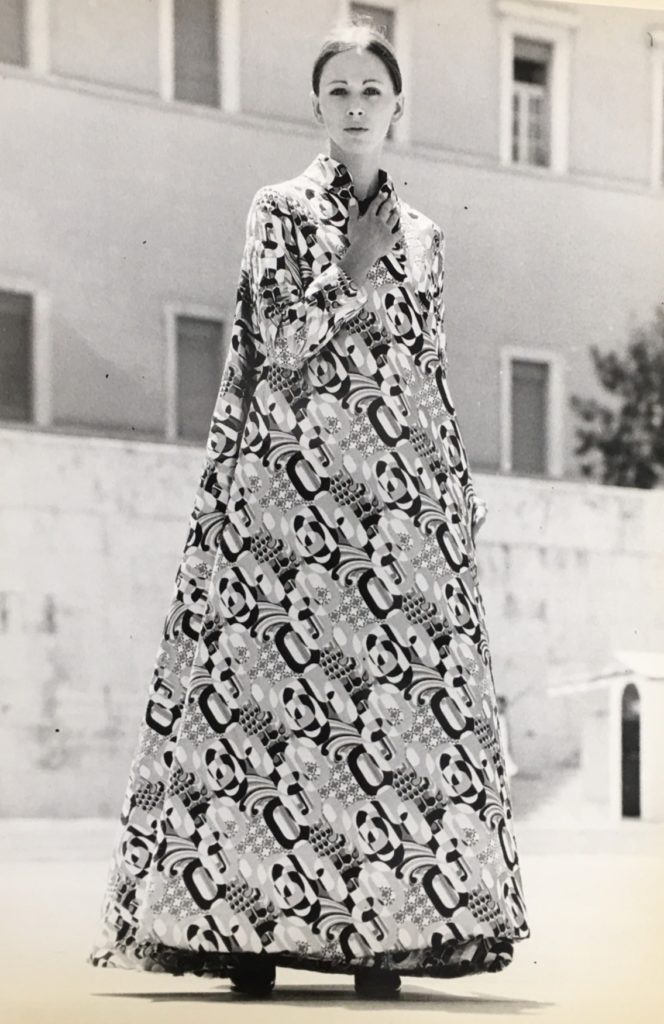

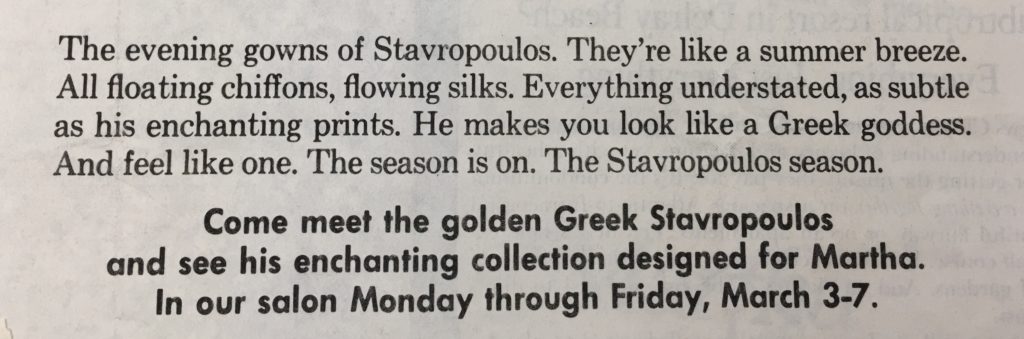

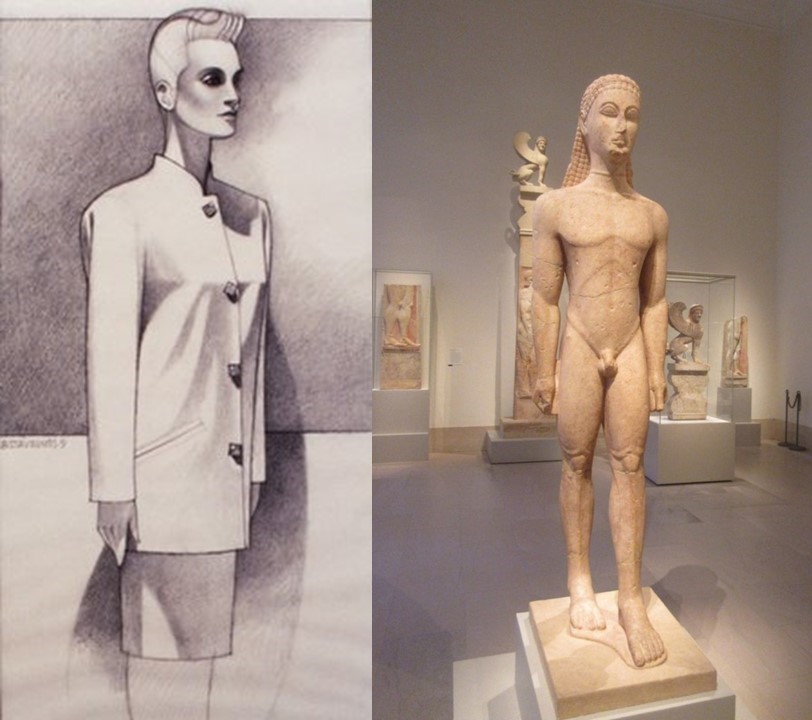

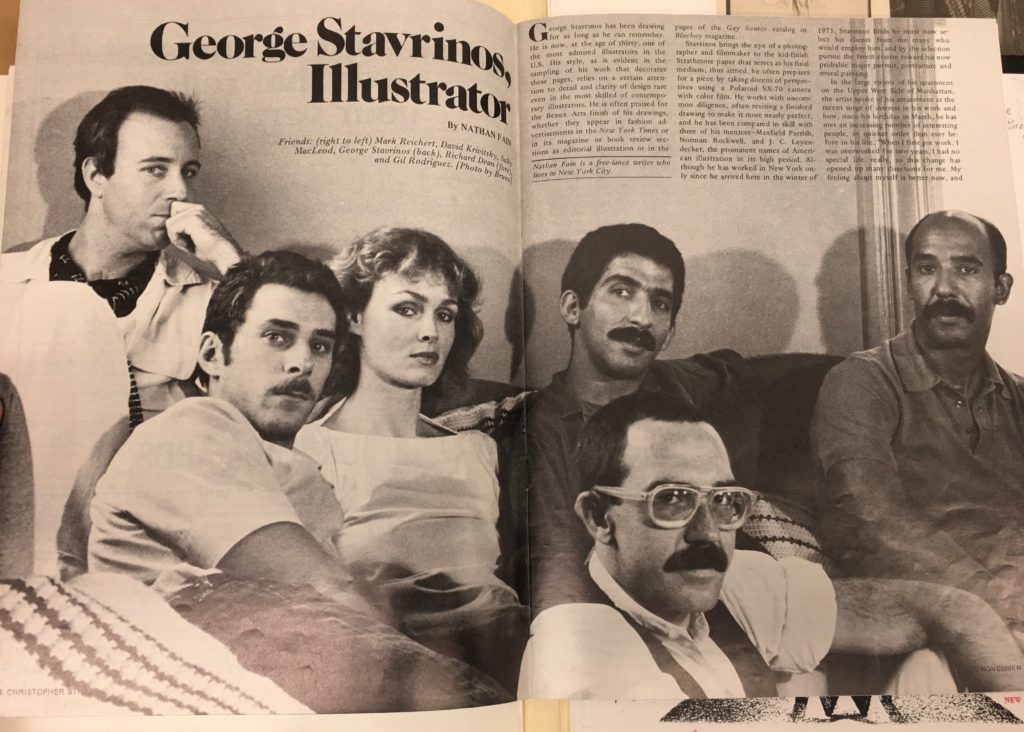

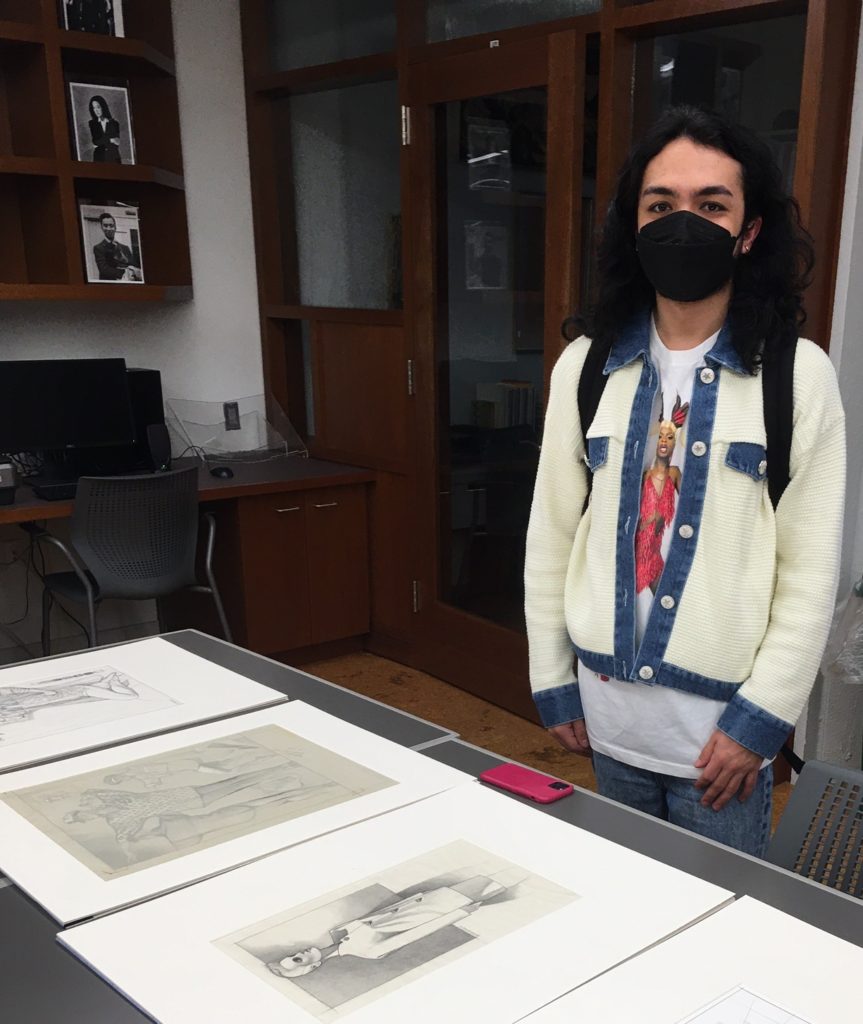

Inspired by the many holdings related to Greece throughout the FIT campus collections, we began research for this exhibition in January 2022. It became quickly evident that there are actually so many exciting archives, materials and stories related to Greek speaking designers, Greek illustrators, Greek influencers and writers in our Museum at FIT and in our Special Collections and College Archives.

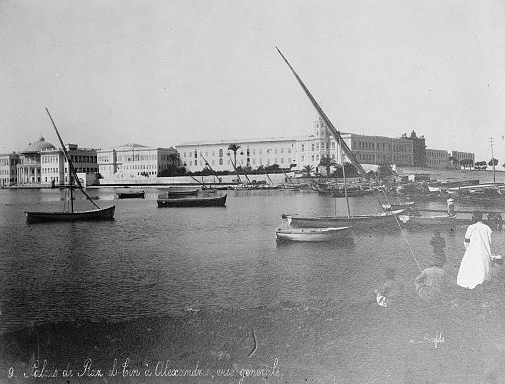

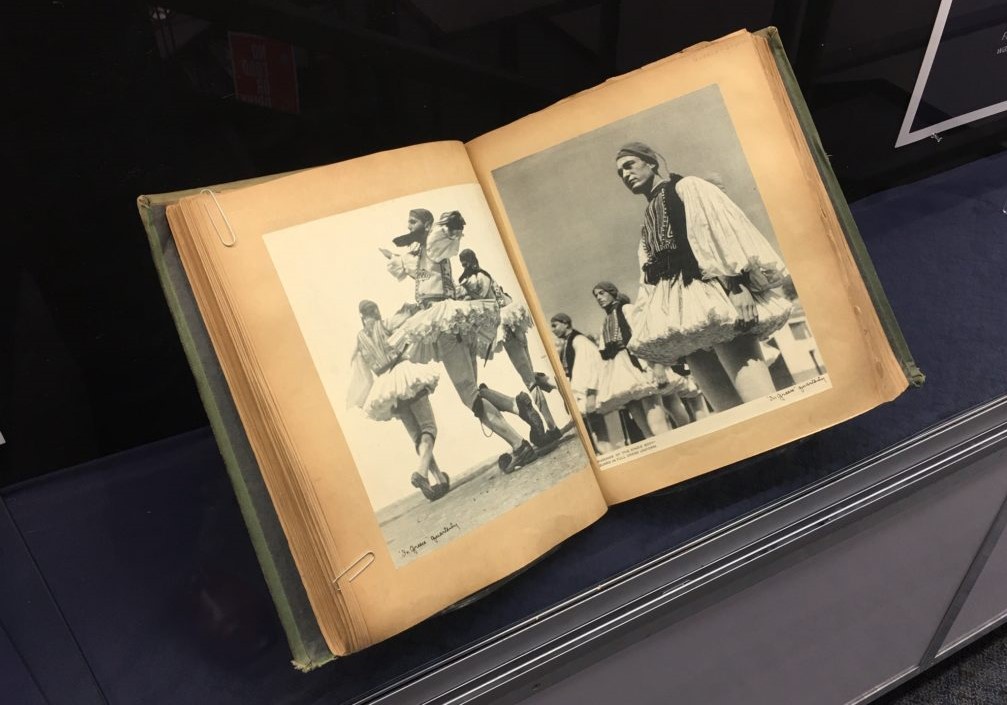

Pre-internet, physical photographs and illustrations were an easy and affordable way to circulate and share ideas and inspirations for young designers. Scrapbooks with postcards and photographs cut out from books and magazines were one way to appreciate and learn about other people and cultures around the world since collecting actual fashion designer’s work for the campus displays in a more organized way did not began in a more organized way until 1969. These early FIT Scrapbooks speak to us in understanding past methods of class-room education in Manhattan, as photographs and archives mattered then as they do today.

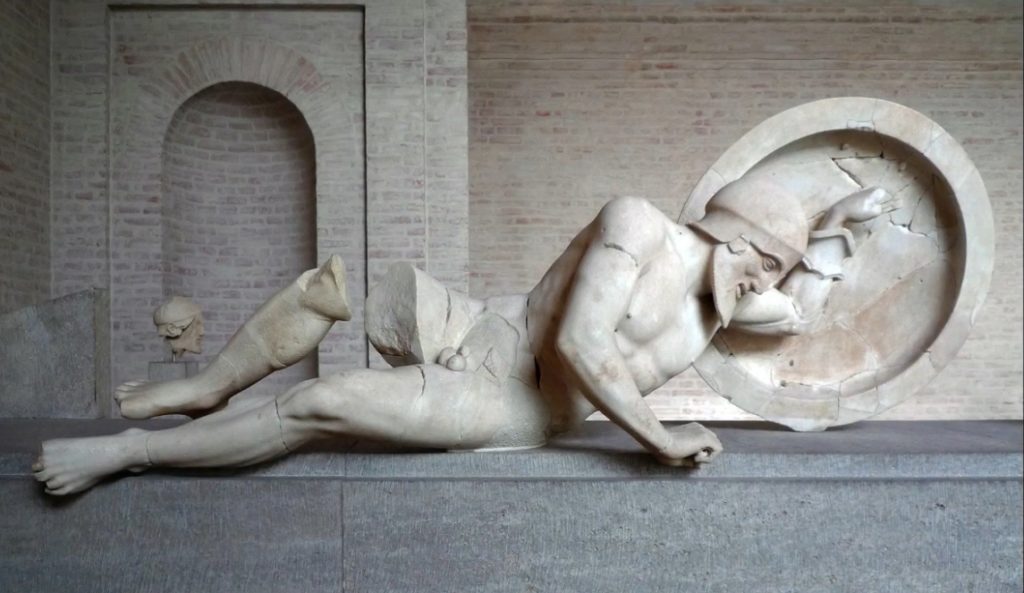

According to a handwritten note, the photograph in this scrapbook compiled by an FIT educator or designer in the 1960s is an illustration cut out a from a magazine In Greece. Quarterly, though no year is given. “Men dancing in traditional Greek costume” is the title of a photograph by Elli Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari, better known as “Nelly” (1899–1998). Nelly’s photographs, especially those portraying people dancing, gained great popularity in the 1930s and later, and she inspired entire generations of photographers. Born in Aydin, now part of Turkey, and spending years in Athens in Greece and in Dresden in Germany, she first arrived in New York City in 1939 with an official mission to assist in overseeing parts of the decoration of the Greek pavilion for a World Fair in Queens.

This is when Nelly’s love affair with New York City began. Soon thereafter, she began photographing sites, people, and events in New York City. One series of photographs featured the New York Easter Parade, a tradition particularly important for Greeks. Nelly owned a Studio on 57th Street close to Central Park and lived in New York City for over 34 years before she died back in Athens in Greece in 1998. Many of her photographs, including some she shot in New York City, were later donated to the Benaki Museum in Athens, Greece. The photograph in the FIT scrapbook displayed connects us to the legacy of a photographer who is not uncontroversial today as is her influence and legacy as a photographer of inter-war Greece.

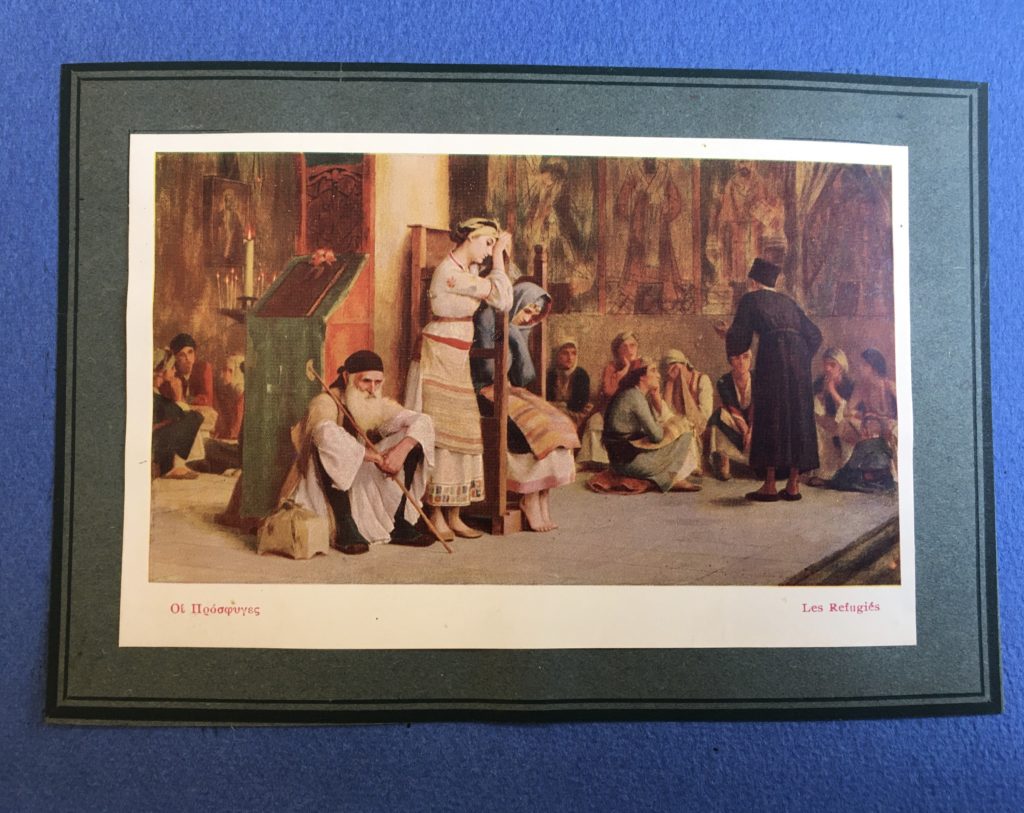

Sometimes there are other stories that develop from engaging with a scrapbook collection and archives such as those housed at FIT. In some cases, the name of the person who compiled the scrapbook is even known. This is the case with a series of little scrapbooks compiled by artist Deirdre Bialo. One scrapbook contains sets of cut out photographs and postcards from Greece. It contains, among many other items a commercial postcard of the painting Οι Πρόσφυγες (“The Refugees”) by Greek artist Theodoros Rallis (1852–1909). Would it not be interesting to sometimes go back in time and listen to the conversations of those who painted, to those who later photographed, those who distributed the photographs and compiled these in scrapbooks?

Further Reading

Damaskos, Dimitris and Dimitris Plantzos, eds. 2008. A Singular Antiquity: Archaeology and Hellenic Identity in Twentieth-Century Greece (Athens, Benaki Museum), esp. “The Uses of Antiquity in Photographs by Nelly: Imported Modernism and Home-Grown Ancestor Worship in Inter-War Greece,” The full volume is accessible online here.

Degirmenci, Erol. 2022. “The Queen of Neoclassical Photography: Nelly.” Daily Art Magazine. March 27, 2022.

FioRito, Taylor, Allie Geiger and Clay Routledge. 2020. “Creative Nostalgia: Social and Psychological Benefits of Scrapbooking,” Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 38.2: 98–103.

Markessinis, Andreas. 2016. The Greek Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Pelekys.

Vogeikoff-Brogan, Natalia. 2021. “The Transatlantic Voyage of a Greek Maiden,” From the Archivist’s Notebook Blog, April 17, 2021.

Zacharia, Katerina. 2015. “Nelly’s Iconography of Greece,” In Camera Graeca: Photographs, Narratives, Materialities, edited by Philip Carabott, Yannis Hamilakis and Eleni Papargyriou. London: Routledge: 233–56.

About the Author

Dr. Alex Nagel is Chair of the Art History and Museum Professions Program (AHMP). He recently contributed an essay on Greek archives and legacies at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. to the volume Legacies of Ancient Greece in Contemporary Perspectives, ed. by Thomas Gerry (Vernon Press, 2022, pp. 23–62). Learn more about his work here.

One Current Favorite Reading or Art Exhibition

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. 2019. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. London: Verso Books.