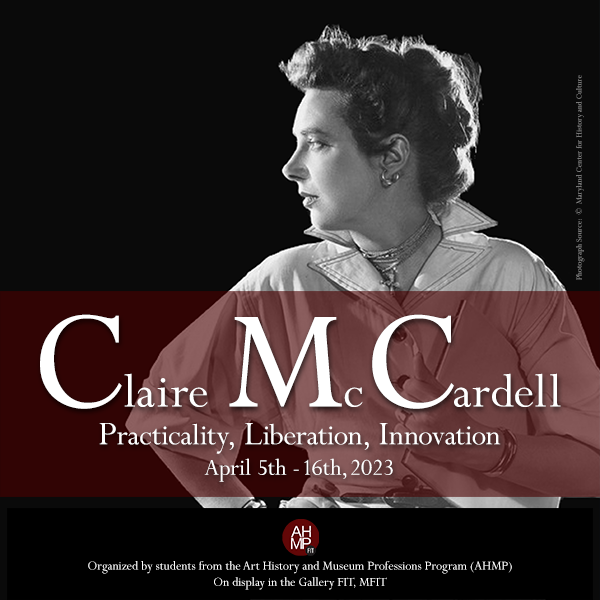

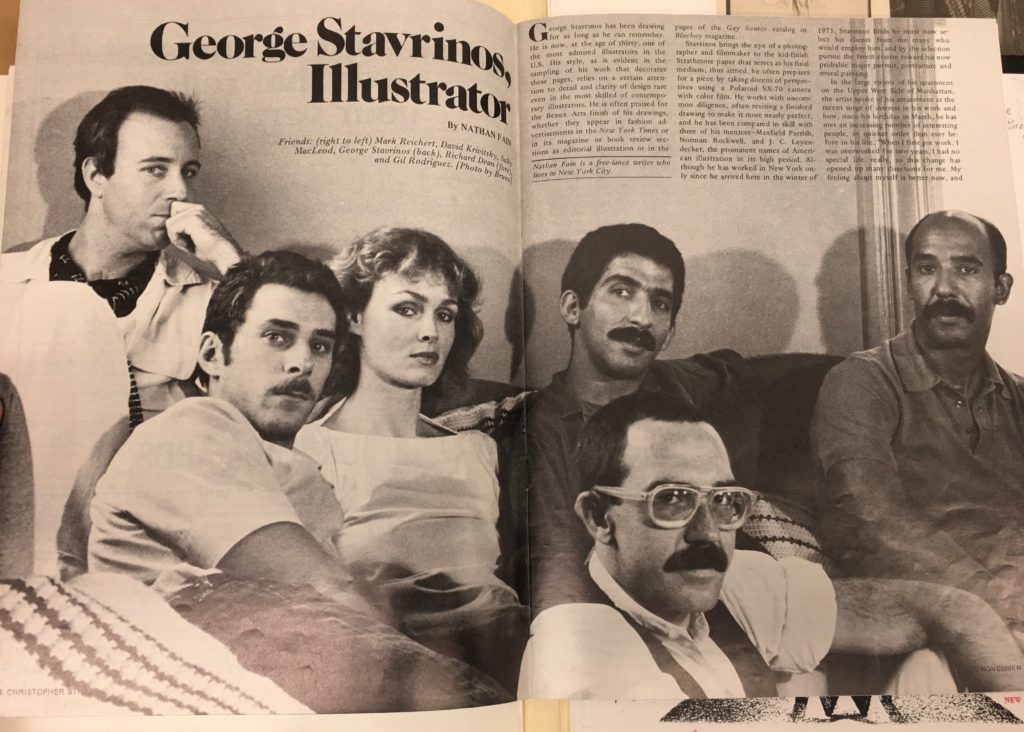

An Interview with AHMP alum and Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) Assistant Curator Darnell-Jamal Lisby, by Dina Pritmani, Friday April 21, 2023.

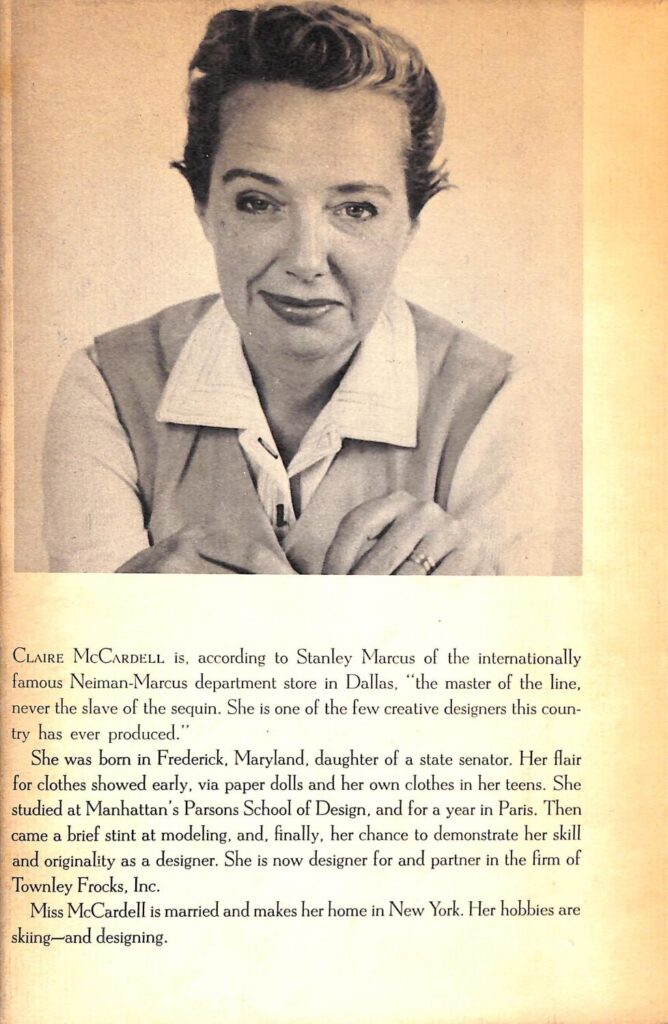

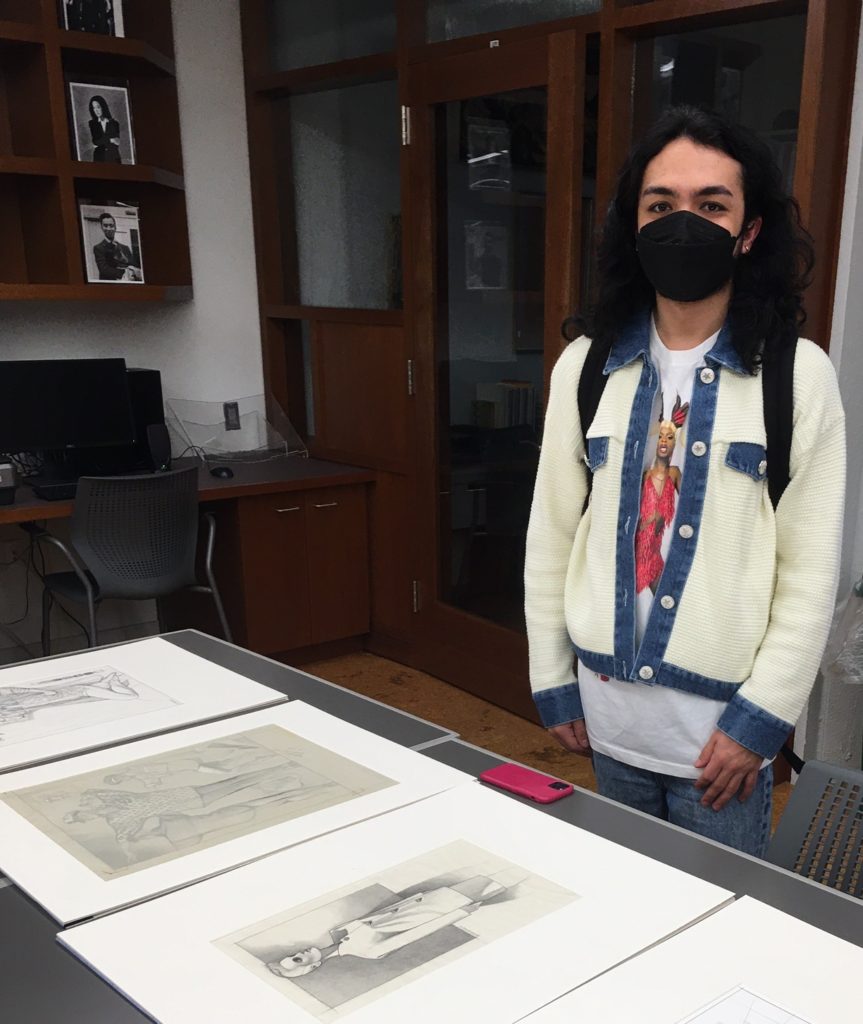

Darnell-Jamal Lisby, Cleveland Museum of Art Assistant Curator of Fashion and Curator of Egyptomania: Fashion’s Conflicted Obsession, currently on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art, sat down with Dina Pritmani, AHMP (’24) to answer a few questions. Darnell joined the CMA in 2021 to develop projects rooted in fashion studies that range across the museum’s various curatorial departments. Before coming to the CMA, he had gained experiences and worked at other institutions such as the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, The Costume Institute of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where as a MuSe intern he helped research the 2018 landmark exhibition Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination, and The Museum at FIT. Darnell is a proud AHMP alum, who has published extensively on academic and mainstream platforms, including the Fashion and Race Database, Cultured magazine, and Teen Vogue. Starting out with an AAS in Fashion Merchandising, he received his Bachelor of Science in the Art History and Museum Professions (AHMP) program here at FIT before continuing finishing his MA in Fashion and Textiles Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice, also at SUNY FIT.

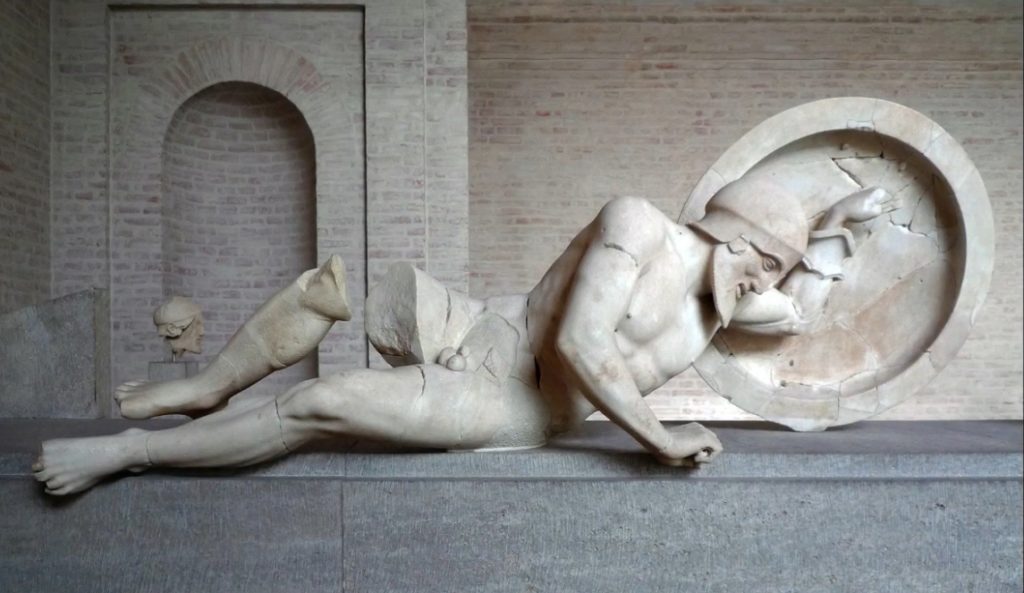

By zenbikescience – Flickr: art museum, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25746245

DP: Many Congratulations on the Egyptomania exhibition! Thank you for taking the time to do the interview. I would like to know more about the background of the exhibition. What inspired you to organize an exhibition with this theme? Why is the topic so important?

D-JL: Like most people, ancient Egyptian culture intrigues me as well. After seeing a handful of recent collections by different ateliers, inspired by ancient Egyptian art, I thought it would be pretty timely to execute the project. Additionally, when I started curating the show, it was the 100-year anniversary of the discovery of Tut’s tomb, so again, I thought it would be timely to produce this exhibition.

DP: How do you create a narrative or theme for an exhibition, and what strategies do you use to engage and educate your audience?

D-JL: Like any curator, you try to find glaring stories that connect the various objects I was thinking about compiling for my checklist. One of which was about cultural appropriation and if it applies to the use of ancient Egyptian culture as inspiration. Finding topics, like cultural appropriation, that connect with contemporary events are accessible ways to engage the audience. Furthermore, I used the broader topic of ancient Egyptian art and culture as inspiration for fashion to peak audience’s interest and then guided them to the denser topics like cultural appropriation and identity.

DP: Could you walk us through the process of curating the exhibition, from selecting the artwork to designing the installation?

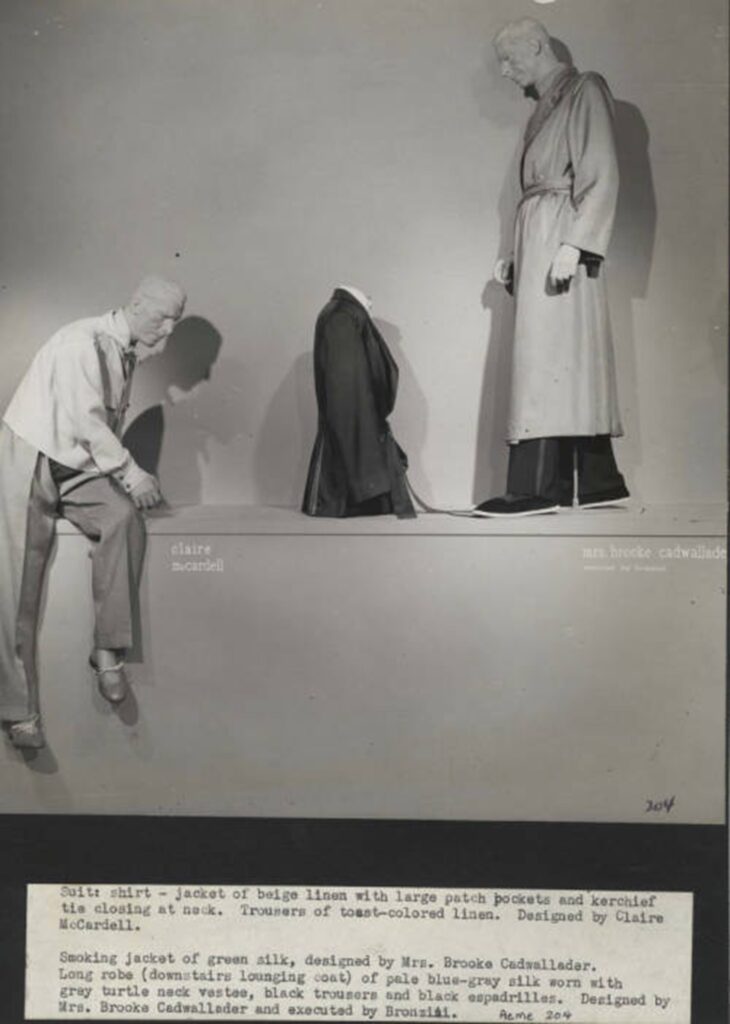

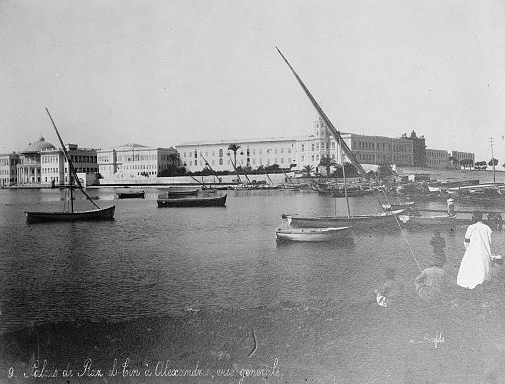

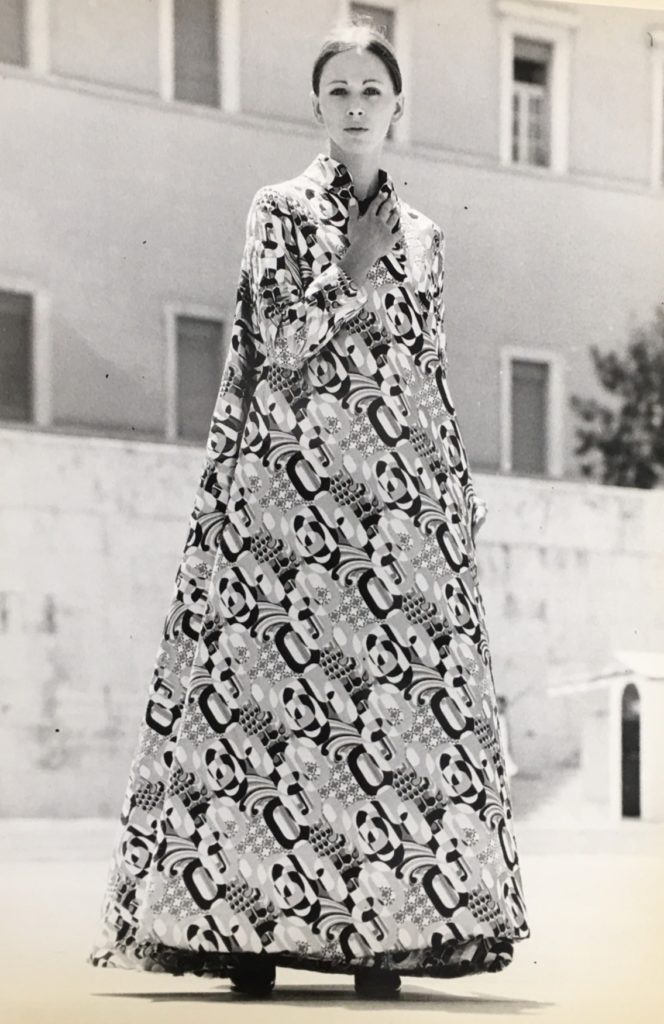

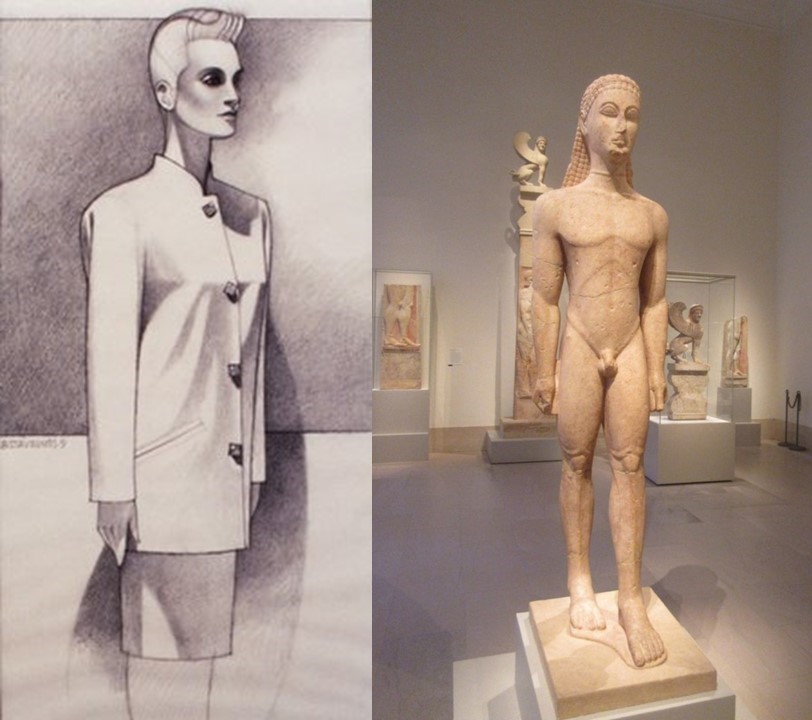

Well, it can get complicated, making it difficult to convey in a few short words. With said, I looked at different topics that I felt inspired to explore such as, cultural appropriation, the identity of ancient Egyptians, and how we and audiences over time connect with ancient Egyptian culture. From there, based on the budget I was given, I had to be very deliberate about which contemporary fashions spoke to the topic as well as ancient Egyptian art from the Cleveland Museum of Art collection that helped support the theses. Additionally, I had to lay out the history of Egyptomania and early Egyptological research that spurred the Egyptomania movement; thus, I had to pull examples across the CMA collection from decorative arts to drawings to help develop that foundation. As part of the CMA strategic plan, which strategic plans help guide the mandates of each museum employee, I also had to think about an intervention in our CMA Egyptian gallery (The second photo attached is of the intervention). Interventions are ways that you can bring outside art into permanent collection galleries, emphasizing new ways to analyze various works of art and collections. I wanted to have one of the fashions that I chose displayed in the Egyptian gallery, in which I chose a Givenchy ensemble from the fall 2016 collection the Givenchy archive graciously allowed me to use. Some of the other houses I displayed include Chanel, Balmain, and Cartier. Additionally, I wanted to highlight Egyptian fashion design voices, so I incorporated two gowns by Egyptian designer Yasmine Yeya for her house Maison Yeya and a purse by Sabry Marouf. Once I developed the checklist, I had to develop the didactics, illuminating what I found in my research that I was developing as I chose the checklist. Once the didactics went through rigorous edits, then it was time to work with the exhibition design team to create the physical show. I worked with them to create the blueprints and what inspirations I wanted to evoke. Lastly, in conjunction with the conservation team, headed by Sarah Scaturro, who was the former chief conservator of the Costume Institute, we figured out what type of dress forms we wanted to use. We also partnered with renowned costume dresser, Tae Smith to help dress the forms. After that, the rest is history… All things considered, the point is that each part of the process requires collaboration with departments from project management and exhibition design to production and conservation. To reiterate, every decision always comes back to the budget. Because I’m starting the fashion department here at the CMA, jumping to have the same budgets as somewhere as the Costume Institute at the MET is unrealistic, so I had to manage what I could with what I was given to do my best to give audiences the best experience as possible.

DP: Who inspired you to become an art curator, and how did you get started?

D-JL: After studying Andrew Bolton’s career way back in high school, it was his journey that encouraged me to become an art and fashion curator. I started just like you, in the Art History and Museum Professions program at FIT, taking in every bit of education and internship experience I could. After finishing the program, I matriculated into the MA in Fashion and Textiles Studies FIT Graduate program, and again, I absorbed as much as I could through my education and internships.

DP: What are some of the challenges you face as a curator, and how do you navigate issues such as limited budgets, conflicting stakeholder interests, and ethical considerations?

D-JL: I think the biggest challenge is just getting institutions to understand the value of fashion in the art historical realm because once that’s understood, life becomes easier from budgets, stakeholders’ interest, and ethical considerations. As mentioned, budgets can be tough, but at some point, you must go with the flow and know that God will provide a path moving forward. Philippians 4:6-7 is one of my favorite quotes to reference, “Be anxious for nothing, but in everything by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known to God; and the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.” Of course, everyone’s path to peace is different, but this is my recipe. I think understanding that also understanding that in a place like Cleveland, which is not a fashion center, my work is going to be a slow burn to get a certain level of international recognition that leads to various degrees of support, from financial to cultural. And that’s okay. I think most people think they’ll be the next big thing, but staying true to yourself and going along with the process will take you where you need to be. I think, especially when I was an AHMP major, we could change the world. That’s still true, but it’s going to take a lot more politicking than one can imagine. Also, being one of the Black curators in the world involved in this work and heading my own department is a blessing certainly that I thank the CMA for, but also using my platform to expand representation in fashion and pulling up others along the way is what I live for.

DP: What are some of the most memorable exhibitions you’ve curated or participated in, and what made them stand out for you?

D-JL: When I helped curate the Willi Smith: Street Couture exhibition with Alexandra Cunningham Cameron and Julie Pastor at Cooper Hewitt, I had the best time exploring the stories of all the people Smith knew during his life and how much they loved him. It was those stories that helped develop the exhibition and accompanying assets. When I curated the Egyptomania: Fashion’s Conflicted Obsession, I found all my research discoveries very exciting too, like understanding that the ancient Egyptians were unified by religion, not racial identity – as race is recent construct in our human history. I also loved dressing the mannequins and physically mounting the exhibition, seeing all the work we did at the CMA come to life.

DP: How do you see the role of fashion curators evolving in the future, and what do you think are some key trends and challenges facing the field?

D-JL: Fashion curators will continue to push boundaries, including searching for new topics that lean into contemporary culture to discovering new contributions by unsung figures and cultures, because fashion is such an accessible medium that touches on so many audiences’ lived experiences. I think the biggest challenge right now for fashion historians is not being afraid to tackle dense topics. As curators, our jobs are to make a complicated topic layman. Moreover, looking to diverse perspectives and celebrating a broader degree of contributions is very important and will help solidify fashion as a critical part of academia.

DP: Thank you so very much for taking the time to answer the questions. Many Congratulations on Egyptomania: Fashion’s Conflicted Obsession!

Egyptomania: Fashion’s Conflicted Obsession will be on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art until January 24, 2024. The exhibition website has more information and extras on related events and more. Follow the work of Darnell-Jamal Lisby.

About the Author

Dina Pritmani is a junior at FIT’s AHMP program, and currently a Facilitator in The Museum at FIT. Dina is passionate about Western Asian Art, jewelry design, and learning about ways to decolonize museums. The interview was an opportunity to discuss these aspects with a Museum Professional as part of an assignment for MP 361 “Museum Professions and Administration.”

Current favorite exhibitions in New York City

The African Origin of Civilization at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Thannhauser Collection at the Guggenheim Museum.