By Emma Sosebee (AHMP’23), Thursday, July 13, 2023

The wives or daughters of fishermen, otherwise known as fishwives, were an essential part of the local economy and culture of Scotland until the dominance of industrialization in the mid-twentieth century made small-scale fisheries obsolete. While their husbands or fathers were off at sea, these women––in combination with caring for their large families––were responsible for cleaning the men’s fishing lines and attaching a variety of new bait, gutting and cleaning the day’s catch in freezing water, and carrying heavy loads of freshly prepared fish for miles to sell at city markets or from house to house. Besides their physically demanding jobs and sharp tongues, these women were also known throughout the country for their distinctive dress. In an effort to increase fashion history scholarship that focuses on working-class communities, this essay will discuss the outfits that Scottish fishwives commonly wore while laboring and for cultural celebrations.

Although existing documentation of the usual uniform worn by these women is unfortunately scarce, past interviews with former fishwives of Newhaven (a district in the City of Edinburgh, Scotland) provide some insight. Their work clothing was relatively simple, and consisted of a navy blue cot, otherwise known as a petticoat, made out of thick flannel; a dark, possibly wool, gown put on over top; and even a white and navy woolen brat––the word for cloak in the Scots language––for days with harsher weather conditions (see fig. 1 and 2). Both their petticoats and dresses were significantly shorter than the ankle-length garments that were common at the time. While they displayed more of the leg than was typical for women’s fashions, the rather practical calf-length gave fishwives greater freedom of movement and kept their skirts clean. To finish off the look, these fisherwomen typically wore dark wool stockings and black leather lace-up shoes with short heels.

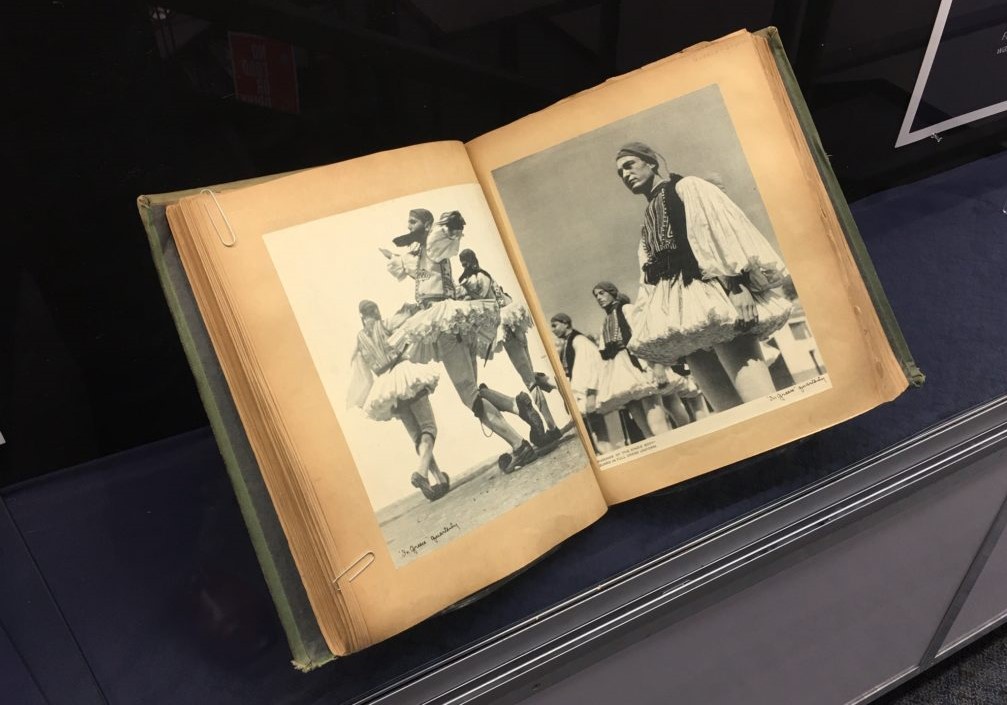

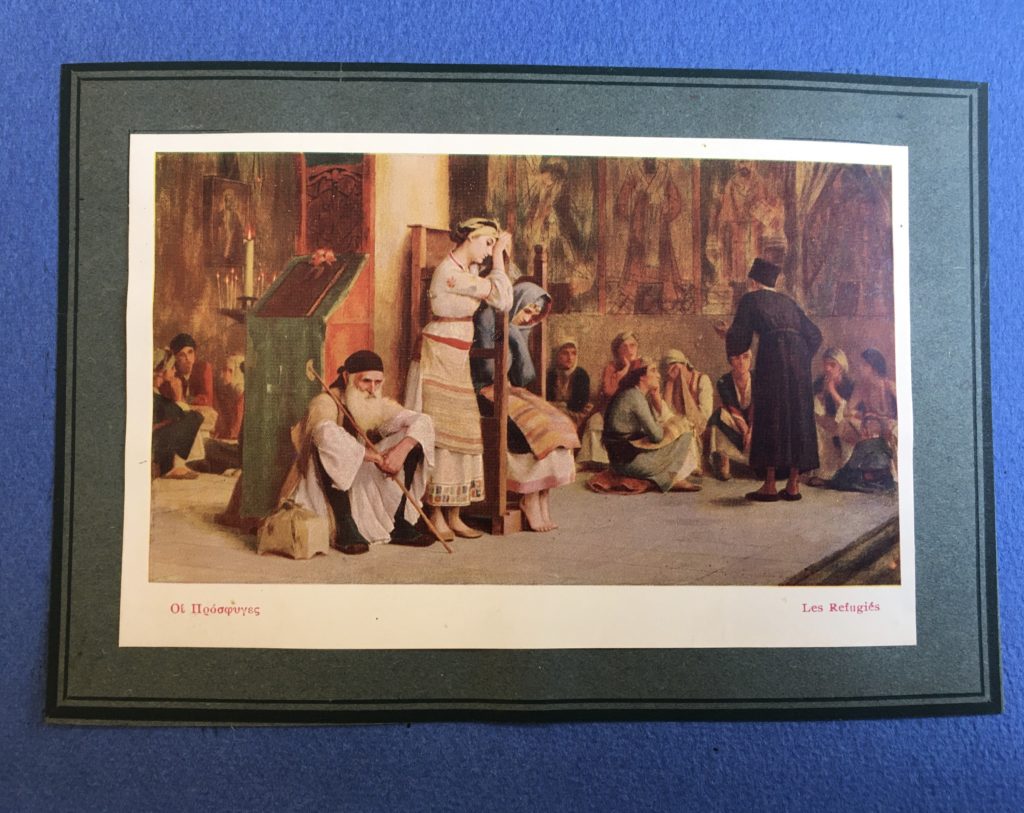

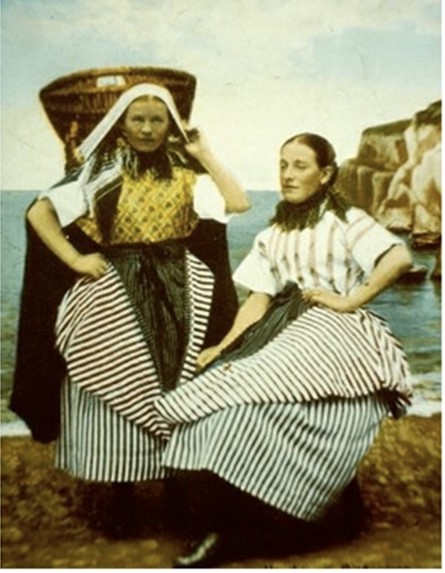

Many historic photographs seen nowadays that exhibit the clothing of Scottish fishwives were heavily staged and thus show the women in their traditional ‘gala-dress,’ rather than their working uniform as discussed above (see fig. 3 and 4). These gala-dresses were worn on special events only; namely, for Sundays, Harvest Thanksgiving and other festivals, and the Fisherlassies’ and Fisherwomen’s choirs. When describing such outfits, the 19th-century writer Lady Eastlake claimed: “With a heavy load of petticoats as of fish . . . She was laden with clothes, petticoat over petticoat, striped and whole color, all of the thickest woolen material.”

Fishwives in their gala-dress were generally observed wearing two layers of heavy woolen petticoats tied around their waists. Both were made of a broad, vertically striped fabric (see fig. 5 and 6). The first petticoat was often made of a vivid red and white material, but the second one’s colors differed depending on location: Newhaven women usually wore yellow and white, whereas those from Fisherrow (a harbor and former fishing village, now incorporated into the town of Musselburgh in Scotland) wore blue and white. The yellow or blue and white petticoats had a kind of padded undergarment, or bustle, to assist in supporting the weight of the creel (i.e., woven basket) worn on a fishwife’s back. A cotton apron of blue and white stripes, pinned to the inside of the second cot, and a medium-sized pooch––the Scots term for pocket (see fig. 6)––were also tied around the waist; as famously shown in depictions of fishwives, their aprons would be kilted up over the top petticoat and pinned to hang in a neat point in the front. Furthermore, the women would don shor’goons, which were long blouses with short sleeves, of various colors and patterns.

The finishing touches to the upper half of the gala-dress were the addition of a broad satin ribbon, tied into a bow and pinned to the wearer’s chest with a brooch, as well as a shawl that would be draped over their head and shoulders. Sometimes, fishwives could also be spotted with stiff white caps over their hair. Similar to their daily outfits, they wore white worsted stockings and high-quartered shoes. What is most interesting is the fact that the entirety of this festive costume lacked any buttons or hooks and eyes; instead of having such efficient closures, which would have required sewing to be attached, these outfits were held together by a multitude of ties and pins and made putting them on quite the hassle.

Both the atypical length of the petticoats seen in the daily, functional uniforms of fishwives, as well as the elaborate and haphazardly assembled outfits they wore on special occasions, undoubtedly stand out in fashion history. As a consequence of the global turn toward industrialization, the economic and social role that such hardworking women of Scottish history played is over; within the last few years as well, the majority of the remaining generation of former fishwives have passed away from old age. Nevertheless, thanks to the documentation provided by charmed 19th and 20th-century writers and photographers alike, the intriguing fashion of these traditional fisherwomen lives on.

About the Author

Emma Sosebee (she/her/hers) is a 2023 graduate of the AHMP program and one of the curators of Claire McCardell: Practicality, Liberation, Innovation at The Museum at FIT (April 5-16, 2023). Throughout her undergraduate career, Emma developed an enthusiasm for how arts institutions care for their numerous objects. She hopes to pursue her interest in the collections management field and is currently an intern in the Collections Department at The Paleontological Research Institution in Ithaca, New York.

Further Reading

Barber, Dr. Karen. “David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, Newhaven Fishwives.” Smarthistory. Accessed April 16, 2023.

Fairnie, Simon, and Dawn Susan. “To the Creel. Fisherrow Fishwives and Their Baskets.” Woven Communities. Accessed April 16, 2023.

Liston, Jane-Ann. “The Newhaven Fisherwomen’s Gala Dress.” A Stravaig Through Time. Newhaven Heritage Centre. Accessed April 16, 2023.

“The Fisherrow Fishwives.” John Gray Centre – Library, Museum & Archive. Accessed April 16, 2023.

“The Newhaven Fishwife.” A Stravaig Through Time. Newhaven Heritage Centre. Accessed April 16, 2023.