By Michael Battista

Industry Coordinator to the Global Fashion Management Program

As a complement to the recent Hong Kong Seminar and its focus on apparel production and the Asian markets, GFM continued onward to Japan for an optional two-day segment of executive lectures and site visits. Here, the scope of our attention expanded to include merchandising techniques at Isetan Department Store, the ethos of home goods and lifestyle brand Muji, a presentation by renowned textile designer Reiko Sudo of the innovative textile corporation Nuno, and a visit to the headquarters of Toyota [cue the abrupt screech of a record stopping]. You may be wondering what a car manufacturer has to do with Global Fashion Management. The answer is actually, quite a lot.

Toyota is one of the largest and most profitable companies in the world. Before these Japanese cars dominated the planet’s roads, it was a family business known as Toyoda Loom Works. Established in 1907, it became an innovator and inventor of a number of textile looms and cotton spinning machines, improving on the speed, quality, and efficiency of mechanical textile production, and ultimately developing the technology towards automation. The company headquarters in Nagoya, Japan hosts a museum dedicated to exhibiting this history and its pivotal transition to car manufacturing on its original founding site.

The significance of Toyota’s contribution to the apparel industry transcends its historical role in loom development and textile production. The company pioneered a highly efficient and agile manufacturing methodology, known as the Toyota Production System, that serves as the foundation for the Fast Fashion models leveraged by H&M and Inditex (the retail group behind Zara), the second and third most valuable apparel companies in the world. Additionally, Toyota’s principals of flexibility, waste reduction, and efficiency are the foundation of the Eton System, used in Esquel’s vertical production plant in Guangdong. During our China seminar, students observed this flexible material handling system, which is designed to eliminate manual handling and transportation, resulting in an increase in production.

While GFM Students explore the fundamentals of agile, efficient, responsive, and risk minimizing production models like the Toyota Production System in the program’s Production Management and Supply Chain course, there’s nothing quite like seeing the application of a methodology with your own eyes. The site visit to the Toyota Commemorative Museum of Industry and Technology, and then later to Toyota Motor Corporation’s Tsutsumi Assembly Plant, offered an additional opportunity for the concepts covered in the classroom to spring to life.

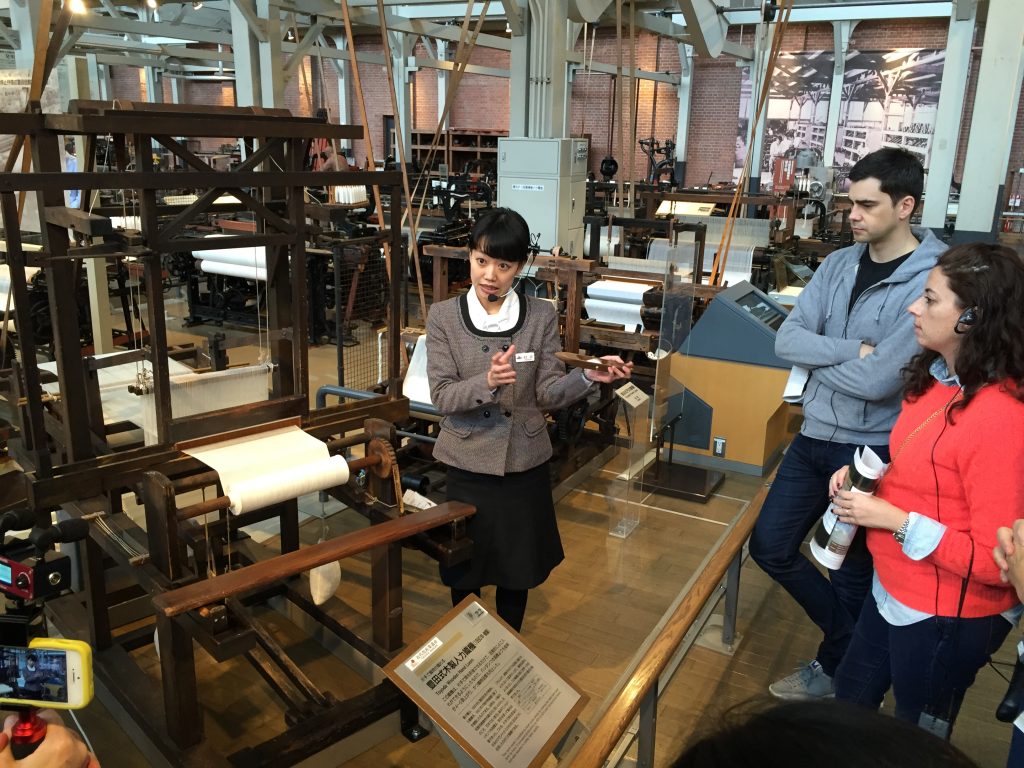

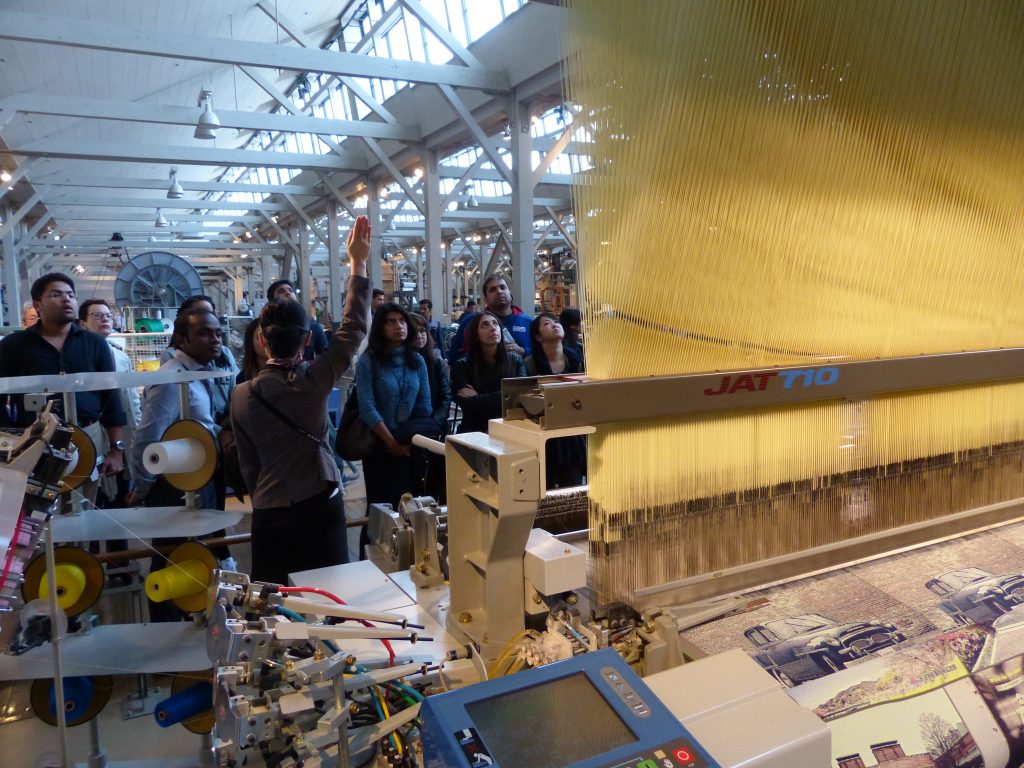

The museum’s textile machinery pavilion is a hangar-sized space of over 11,000 square feet filled with nearly 100 pieces of equipment from its archive—many of which are functional—that showcases the evolution of cotton spinning and textile looms from the industrial revolution of the 18th century to today. Docents lead us through the exhibition, charting the historical progression of these production processes and stopping to demonstrate the machinery along the way. As we proceeded, we witnessed the evolution of technology, speed, and complexity, from wooden machines powered by hand to those forged by steel and guided by computer.

Compared to the more contemporary and dizzyingly fast machines used by factories today, the earlier wooden looms from the beginning of the 20th century have parts that move at speeds more amenable for the human eye to process. For those of us on the tour without a technical background in textiles, it was an opportunity to better see and understand the mechanical process of a loom shuttle moving yarn back and forth between the vertical warp threads to create fabric. It was truly an aha moment for many of us, with the cadence of clicking heard from students and looms alike.

Additional wings of the museum are dedicated to the company’s transition from Toyoda Loom Works to the Toyota that we know today. The most salient changes resulted from the generational shift in management from father to son, and a culturally astute rebranding that altered the company’s name to allude to “good fortune” in the written Japanese language.

By bus, we continued our site visit to the Toyota Motor Corporation Assembly Plant in nearby Toyota City. We ascended to a network of catwalks perched above the production lines. From here, we bore witness to a focused and coordinated effort of man and machine. There was a great deal of activity. Workers were staged across various points of the production lines, diligently and swiftly transforming frames of steel into cars by methodically adding its components. Small robotic carts tugged bins filled with parts to their respective stations. There was a symphony of coded tones and musical notes to indicate production status, delays or errors. This is where we could see and hear the Toyota Production System’s deployment of two of its core philosophical principles:

Just-in-Time: where the supply follows the demand, this is defined by Toyota as “making only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount needed.” Each car we saw on the production line, represented a sale and customer order for that specific model.

Jidoka: a Japanese word at the intersection of automation and human intelligence has come to embody a quality control methodology to prevent defects throughout the workflow. Assembly workers stop the production line if a problem arises or is detected before the car moves forward to the next step in the manufacturing process.

Toyota’s growth and capture of the global market share is due to its development and refinement of these core principals (among others), which have enabled it to maximize efficiency and minimize waste (waste, in this case, being defined as overproduction).

The history of this company’s success across generations and industries illustrates the value of internationalism and open trade. Both generations of Toyoda leadership were informed and inspired by site visits abroad, building their respective global empires on the foundation of their impressions of best practices and innovations, and ultimately improving on them. Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of the company’s first incarnation, visited the global textile centers of his day, touring fabric mills in the northeastern U.S. and Manchester, England. His son, Kiichiro Toyoda, who transformed the company into an automobile manufacturer in 1937, went to see the Ford operation in Detroit at the onset of its development of the Assembly Line Method, a transformative innovation in manufacturing at the time.

For a grand finale, we witnessed the mechanical ballet of the welding machines fortifying the frames of cars-to-be, rhythmically moving to the beat of their own programming. Many large mechanical arms swiftly and articulately moved in concert across the body of a single car. They stretched, contracted, and rotated around each other, sending bursts of orange sparks into the air. At this point on the catwalk, we stood entranced by the performance, which would end within a minute’s time, only to be repeated on the next car frame in line. The speed and scale of the elegant process was both impressive and humbling. Many jaws had fallen ajar at the sight of it all. As we stood there above the manufacturing line, I could do nothing but appreciate that after nearly 80 years from the company’s inception, we were witnessing the fulfillment of a vision of automation, efficiency, and synergy of human and machine. And so I wondered, what potential advancements might lie on the horizon of the apparel industry’s future, and what visions have yet to come?