By Pamela Ellsworth

Chair, Global Fashion Management

GFM Seminar: April, 2018

This year’s Paris seminar was devoted to an understanding of the professional organizations established to support France’s legendary fashion industry. In addition, the multicultural team assignment was created to provide a deeper analysis of the design inspiration of current couture members. Fascinated as we tend to be by the Paris collections for their creative beauty and extravagance, as well as for their excess and occasional insanity, it’s easy to forget that they thrive and contribute to France’s economy based on the strength of powerful state-run organizations.

David Zajtmann, Creative Brands Strategist at Institut Français de la Mode, and author of Understanding the Role of Professional Organisations in Supporting the Creative Industries writes, “the presentations of collections in Paris remain important events for the global fashion industry thanks to a long-term strategy of strong professional representation, regulation and integration of national and international key industry players carried out by the Fédération over time.” Mr. Zajtmann presented to GFM on the first day of the seminar, laying an essential foundation for the following several days of immersion into the structure of the organization and the creators that uphold its reputation.

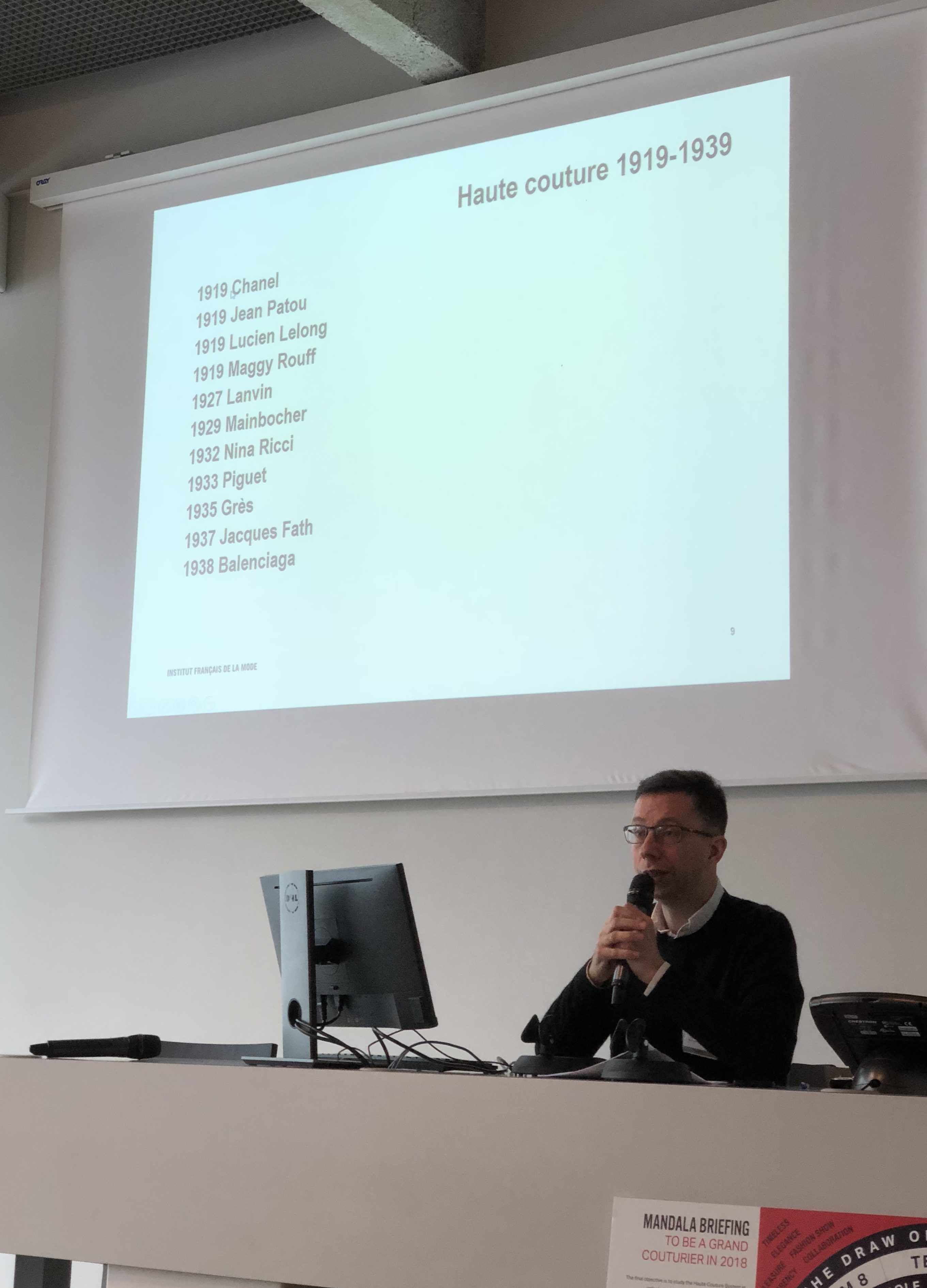

By the end of the seminar, our knowledge of the Parisian fashion system – the introduction of the couturier in 1858; the creation of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne in 1911; the rise of ready-to-wear in the 1960s; and the establishment of the Fédération de la couture, du prêt-à-porter des couturiers et des créateurs de mode in 1973 – helped us to understand the methodology and evolution of what is still the world’s most well-developed fashion system. In his article, Mr. Zajtmann discusses the French government’s supporting role in establishing a list of authorized couturiers every year, and, until 1979, even financing the purchase of French fabrics to be used in the shows, in addition to making it possible for fashion companies to host fashion shows at the Louvre until 1986.

This historical insight and much more – as we heard from a broad range of speakers at the IFM’s YSL Amphitheatre as well as at site visits – provided essential background in making comparisons and contrasts to the company structures and organizations we would visit when we continued on to Florence and Prato, Italy at the close of the Paris seminar.

Our brief seminar in Florence and Prato was organized to introduce GFM graduate students to a textile and fashion system that was culturally, historically, and organizationally different from the Paris system of haute couture we had just experienced during our 10-day seminar at Institut Française de la Mode.

We organized our two-and-a-half-day Italy seminar with the guidance of Pascal Gautrand – a founder of Made in Town and a consultant for Première Vision – a French colleague who studied at the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome, and has worked closely with Italian companies in recent years. In his introduction to our students, he described the unique history of Tuscany as the inspiration for the region’s ability to manufacture luxury goods since the Middle Ages, and how Italian companies are reinventing their heritage to survive in today’s highly competitive business climate.

We began our seminar with a private meeting in the conference room of Pitti Immagine, with Raffaello Napoleone, the CEO. This organization is devoted to promoting the Italian fashion industry, and is perhaps the most important trade show for menswear in the world. Mr. Napoleone began with an overview of the American Marshall Plan’s impact on the Italian fashion industry following World War II, continuing with statistics on the large volume of Italian women’s fashion purchased by American department stores post war, and describing the struggle to compete in the 1970s based on the small size of individual companies and lack of organization, resulting in the industry’s move to Milan. Mr. Napoleone has reinvented Pitti Immagine from a conventional trade show to one that reaches beyond fashion to a cultural strategy, by offering a research division, art, architecture, food, wine, and fragrance. He commented that because fashion can change easily and be communicated quickly, the trade show must reinvent itself season after season.

As one of the most high-profile business executives in the Italian and European fashion industry, we knew that Mr. Napoleone didn’t have a great deal of time to spend with us, but none of that seemed to matter as he answered every question around the table (and there were many), even leaving time to make recommendations for the best spots for lunch in Florence. Happily, we could think of no place farther from New York City, and no one more generous or knowledgeable in relating the details of the Italian fashion industry.

Our next stop was Scuola del Cuoio, a leather school founded by Franciscan friars after World War II, located near the banks of the Arno River, which has been the location of the leather tanneries since the 13th century. The portion of the building that we visited was donated by the Medici family during the Renaissance, with the photo below showing one of the frescos from that time.

From Scuola del Cuoio, we visited the Palazzo Pitti’s Fashion and Costume Museum, a shrine to some of the most extraordinary costumes and contemporary garments in the world. The Museo della Moda was founded in 1983, and contains haute couture Italian design, cinema, and opera costumes, and a rather astonishing display of the funeral clothes of Grand Duke Cosimo de Medici and his wife, Eleonor of Toledo. (Their bodies were disinterred, and the bones and textiles were examined.)

By bus, we headed out of Florence to Fiesole and the Stafano Ricci atelier. Mr. Ricci explained the brand heritage, and his staff toured us through the small custom shirt and belt factory. You won’t see any photos because we were sworn to secrecy, but the small-scale atelier of beautiful quality Italian cotton shirts was unlike any productions facility we would find most anywhere in the world.

We continued north to Il Borgo San Lorenzo to visit Il Borgo Cashmere, a family-owned company since 1949 where research and experimentation is based on ancient craft techniques. Here, the company knits luxury garments and home products for Loro Piana, Bergdorf Goodman, and other high-end retailers and major fashion houses. In this small town, the company’s artisans train local crafts people to hand knit some categories of product out of their homes, which means that the company devotes considerable resources to time management and quality control, while still encouraging a spirit of creativity. The European Union finances a good part of this training. We were struck by this community dynamic, but had to keep in mind that its origin lies in the guilds of the Middle Ages, a system common throughout Europe.

From Il Borgo, we moved on to Capalle and Lineapiu Italia, an extraordinary company that designs and produces specialty yarns for designer fabrics. The company also serves as a repository for the research and protection of Italian sartorial art, housing more than 33,000 archived products, and providing trend direction. They worked extensively with Armani, for example, to develop new ideas and technologies for knits. Hermes and Chanel are also customers. The company runs two mills where they spin mohair, alpaca, cotton, and wool, and they took great pride is walking us through the combing, carding, and sliver phases, preparing the yarn for the knit machines.

As we visited these small-scale, high-quality businesses, I was reminded of political economist Francis Fukuyama’s description of Italian companies in his book Trust, where he draws parallels between a culture’s characteristics and its prosperity. He argues that because of the nature of social capital in Italy, family bonds tend to be much stronger than those between the individual and the state, and where “private sector firms tend to be relatively small and family controlled, while large-scale enterprises need the support of the state to be viable.” Fukuyama is careful to distinguish Italy’s highly productive “Terza Italia” (third Italy, which includes Tuscany) from the impoverished southern portion of the country. He suggests that the networks of small businesses – such as those we visited – represent “an entirely new paradigm of industrial production, one that can be exported to other countries. Social capital and culture give us considerable insight into the reasons for this miniature economic renaissance.”

The vulnerability of the small enterprises that we visited – their locations remote from a large, experienced work force, and dependent upon a rapidly-changing and quixotic luxury consumer – stood in sharp contrast to the depth of creative and manufacturing talent and commitment that we witnessed in every business. In describing the manufacture of the competitive products from the Terza Italia, including textiles and apparel, Fukuyama writes, “This confirms that there is no necessary connection between small-scale industry and technological backwardness. Italy is the world’s third-largest producer of industrial robots, and yet a third of that industry’s output is produced by enterprises with fewer than fifty employees.” Since this book was written, the point about robots is no longer a fact, but Fukuyama does make a strong case for the advantage of sophisticated, small-scale, highly skilled enterprises, based on their ability to adapt to changing consumer markets. Especially for those of us from the U.S. who have been made weary by the magnitude and monopolies of our retailers, we’re rallying to the side of Italy’s artisanal luxury designers and manufacturers to prosper.

Our final stop was a guided tour of the Prato Textile Museum, which occupies a building and location that had been the site of textile manufacture since the Middle Ages. Prato’s textile history has enjoyed enormous success and has more recently suffered great defeat under global competition, but as often as they’ve reinvented themselves, their identity remains closely tied to the textile industry.

Since the focus of our study in Italy was creativity, makers, and manufacturers, our dinner location was no exception. In Fabbrica – the name of the restaurant, which also means Factory – is a silver workshop dating back to 1902. Above the factory on the second floor, we enjoyed dinner by candelabra manufactured on site, where the wait staff worked as artisans just hours prior to our arrival. (The chef, fortunately, was a specialist in food rather than precious metals.)

On Saturday morning, our last day in Florence, we met at the Polimoda campus where Luca Marchetti, Professor and Researcher at the Ecole Superior de Mode at the University of Quebec in Montreal, delivered a lecture to GFM and Polimoda students. Professor Marchetti, who is from Italy and where he also studied, spoke about the socio-historical roots of Italian culture, making comparisons to France along the way. He defined Italy as a country with a “chaotic urban context” and one without a major social revolution, based on what he referred to as unstable and ephemeral power, as compared to France’s more orderly and defined regimes.

We felt that this brief visit to Tuscany could be the start of a much deeper exploration, comparing two of the world’s most important cultural centers. In Paris, we studied the structure and well-developed organization of haute couture and prêt-à-porter – a legacy with well-established roots in the luxury manufacturing and export of 17th century France under Louis XIV. Italy’s small and widely scattered companies, on the other hand, reflecting its history of warring city-states until the 19th century, still struggle. But the dominance of China, Italy’s languishing export numbers, and the trend for ever faster fashion are not what we were thinking about as we witnessed the beauty, creativity, and superior quality of the products we had the privilege to see during our final two seminar days, as well as the humility and generosity of company hosts and artisans. We all agreed that the world would be a much poorer place without Italian and French fashion and the people that create it.