The Great Depression, with its pitiless lessons of economic ruin, cast a shadow over my family, as it did for so many others who managed to scrape their way through the 1930s. It was always there, hovering over the shoulders of my mother and father as they set out to make a life for themselves. I think about this as I reminisce about my family in the context of Black History Month with its theme: The Black Family: Representation, Identity and Diversity. As someone who, many years ago, studied, wrote, presented, and chaired task forces on the Black family, I am well aware of how complex the subject is and that its “representation, identity and diversity have been reverenced, stereotyped and vilified from the days of slavery to our own time,” as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History says.

That my small family managed to survive the Depression and the years that followed, when my sister and I were born, is a matter of faith, fortitude, and hard, hard work. We were not that stereotypical broken, dysfunctional Black family so often written about—but neither were we the upscale professional Huxtables nor part of the expanding nouveau riche middle class (á la the Jeffersons), for that matter. But we were not all that unusual, either. Despite the history of racism that savaged African American life, we were among those many Black families that managed to move, slowly and at great sacrifice, into the fledgling middle class.

My parents met in Harlem during the Depression years, when Blacks from the south were streaming in as part of the Great Migration. Many families met and began that way. Just a decade earlier, Harlem had been home to a great cultural renaissance, a glamorous and dynamic time that attracted luminaries like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, Bessie Smith and Romare Bearden, W. E. B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey. But much of that faded with the onset of the Depression.

My father’s family came from Virginia, and he was born in New York City. My mother’s family was from New Orleans, where she was born. She and my grandmother left for Chicago in search of a better life. I don’t know the precise circumstances which prompted them—or my father’s family—to leave. I rather like what the author Isabel Wilkerson said in reflecting on those who went north: “They left on their own accord for as many reasons as there are people who left. They made a choice that they were not going to live under the system into which they were born anymore and, in some ways, it was the first step that the nation’s servant class ever took without asking.”

As devastating as the Depression was for the rest of the country, it was that much worse for much of Harlem. Certainly some escaped its ravages, and some neighborhoods continued to do well, but as a whole the area suffered from dire unemployment, increased poverty, and deteriorating health and living conditions.

Despite those woes, Harlem retained its vibrant, exciting nightlife, its commercial heart emanating the glamour of show business, its celebrated nightclubs and speakeasies thriving with big bands and dancing showgirls, as if the jazz age had never ended.

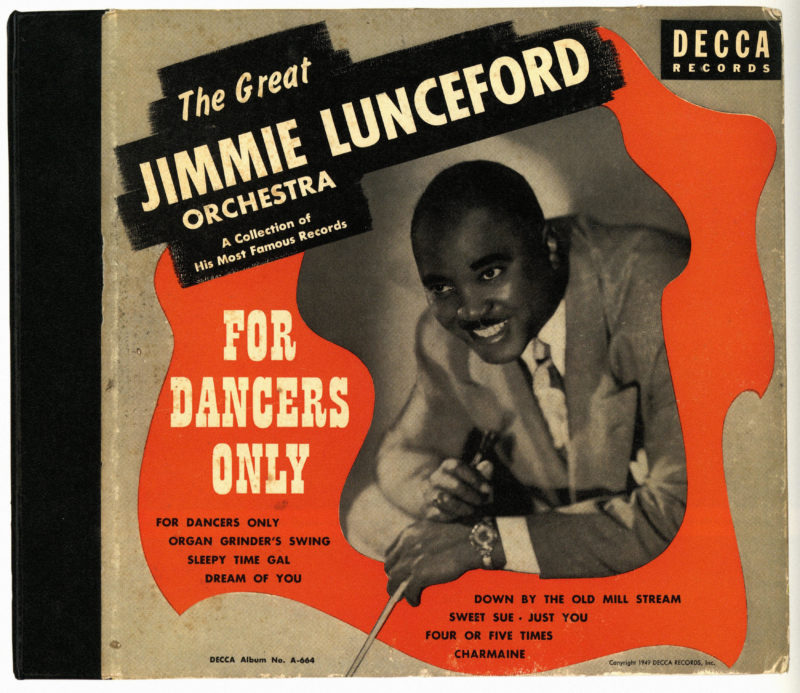

It was at this time, and into this environment, with its mixture of highs and lows, bleakness and bright lights, that my father made his way as a young man. Although he was not an entertainer, he was drawn to the vibrancy of show business and became associated with, and traveled with, the Jimmie Lunceford Band, one of that era’s best known swing ensembles. Quiet and cautious, he neither drank nor smoked, but surrounded himself with creative entrepreneurial people.

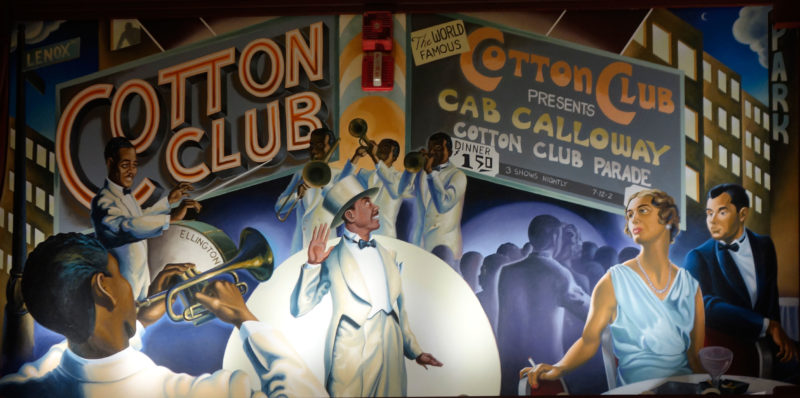

My mother grew up in Chicago, supported by her mother, whose skills as a seamstress I have bragged about at length here at the college. It was my mother’s talent as a dancer that brought her, and her mother, to New York. By the time she was 16 or 17, she was a member of Harlem’s storied Cotton Club chorus line. The Cotton Club also hired my grandmother to design and make its costumes. Eventually, my great-grandparents joined them as did my great uncle when he retired from the merchant marines.

Mother joined the club in its 1930s heyday. She rubbed shoulders with Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong and Lena Horne. In fact, when Ms. Horne was called upon to dance, mom was her understudy. Mother was never a featured dancer but was proud to occasionally be selected as the last dancer on stage—a coveted position.

Unlike my dad, my mother did not relish the life and talked about it very little. If she, or my grandmother, were offended by the “whites only” audience policy, she never said. If she was ever unduly bothered by men, she never said. She once did say that keeping a smile on her face while dancing was difficult because people were not very nice to each other. In fact, it was a hard, demanding life—physically strenuous—and one she adopted only after dropping out of school to help support her family.

Fast forward a decade and more, and my parents, my sister and I are living on Convent Avenue, in the heart of the Hamilton Heights/Sugar Hill district, right across the street from the City College campus. Not far away is Lewisohn Stadium, the then-famous amphitheater where the college’s commencement was held, as well as athletic events and classical concerts It was—and still is—an iconic residential neighborhood, filled with handsome old buildings that once was home to the likes of W. E. B. DuBois, Thurgood Marshall, and Count Basie. And it was within this conclave of blocks and historic buildings that I grew up.

My father always wanted to own his own business and never wanted to work for anyone else. He had an entrepreneurial spirit, but very little luck and very little money. For several years, he tried his hand at a couple of small businesses which he ran with my mother. They worked very hard, but unfortunately, each of the businesses failed. So in the end, both of my parents took steady office jobs, he with the post office, she with the New York City Housing Authority. For them, it was a matter of survival. They were determined that my sister and I would have a different kind of life—a better life—and that life would be achieved through hard work. On this, my parents were as inflexible as steel: This was the American ethos, for blacks and whites and everyone else, the American belief that with hard work and sacrifice, each succeeding generation would rise on the socio-economic scale, and would do better than the last. As a measure of what my mother thought of her life as a Cotton Club dancer, she ruled out dance lessons for either of her daughters. Instead, she bought a piano so that my sister and I could learn how to play—which was what every respectable child in that era was meant to do.

The church played a role in our household as well. I was sent to Catholic schools from K-12, despite its costly tuition. And there was no question about college. College was the ticket to transformation—an education was the one thing no one could ever take away from you. I drank in this message and was mesmerized by the City College students I watched for hours out our windows as they emerged from the subway at 145th Street and streamed down Convent Avenue, clutching their piles of books, looking so smart and serious. I wanted to be just like them.

When I reminisce about family, I also think about two other people: one was my maternal grandmother, the seamstress, with whom my sister and I stayed every weekend in the years my parents had their businesses. Somehow she managed to open a business of her own. I vividly recall the long table of sewing machines and ladies sitting at their stations, stitching garments that were sold under famous designer labels in Fifth Avenue department stores. She made all of our clothes: if I could describe it, she could drape it and make it. Quite often, we would all go with her to Macy’s Herald Square to select fabrics and finishes for whatever ensemble was being created for one of us. To this day I love the touch and feel of fabrics and wonder at the miracle that talented designers and seamstresses can create.

And then there was Lois, a family friend who owned a hair salon. I called her my aunt, and she was like an Auntie Mame—always lighthearted, always fun, almost always with a drink in her hand. From the time I was nine, I would finish up my household chores on Saturdays and then run to her salon where I would do anything just to be there: sweep the hair on the floor, put change in the parking meters for her customers, run whatever errands needed to be run. None of this was for money—although I received a dollar for the day and tips from the ladies, so I never had to ask my parents for an allowance ever again—but just to bask in its special ambience and the sense of belonging that has remained with me to this day.

Of course I went to college: Marymount in Tarrytown, a fine women’s liberal arts institution—also Catholic—that is today part of Fordham University. And then it took me 10 long years of work and study to complete my PhD from NYU.

So you see, there are many ways that Black families not only survived, but built legacies. Black History Month offers an opportunity to remember and reflect on what we have learned from our own family histories. What my parents’ generation had in common was the haunting specter of the Depression. From them, from the church, from the rest of my family, I learned discipline, determination, and sacrifice. From them, too, I learned that failure was not an option—I would have to excel. I learned to never give up on my goals and that, especially as a Black woman, no one was going to hand me success. I learned, as well, that it is possible to make a difference in the world and that, though it is a cliché: to those to whom much is given, much is expected. And as I look back on my family, much was given. As one sociologist put it: “The richest inheritance any child can have is a stable, loving, disciplined family life.” By any standards, mine was rich indeed.