In this brave new world, designers and techies are trying to apply new technologies to improve a very old one: clothing. The history of clothing, fashion, culture, and technology are deeply embedded in the history of textiles. I started to write about new tech developments in fashion and fabric, but then I got excited, as I always do, about the ancient history of textile technology. Archaeology keeps bringing us updates, so I thought it would be fun to review the latest research about the four fibers we use most: silk, linen, cotton, and wool.

The four most popular natural fibers processed into woven textiles have long histories:

Silk finds can be dated to c. 8500 B.C.E. in China. We don’t know if these are the remains of clothing or just evidence of the silk worms themselves. Old stories suggest that this area was the original place sericulture (raising of silk worms and preparing silk thread for use) began.

The traditional Chinese myth is that Lady Hsi-Ling-Shih, wife of the Chinese emporer c. 3000 B.C.E., discovered silk’s fiber properties when she accidentally dropped a silkworm cocoon into her tea. Maybe she did and maybe she didn’t, but we do know that woven fragments of silk, dating from around 3000 B.C.E were found in Zhejiang province.

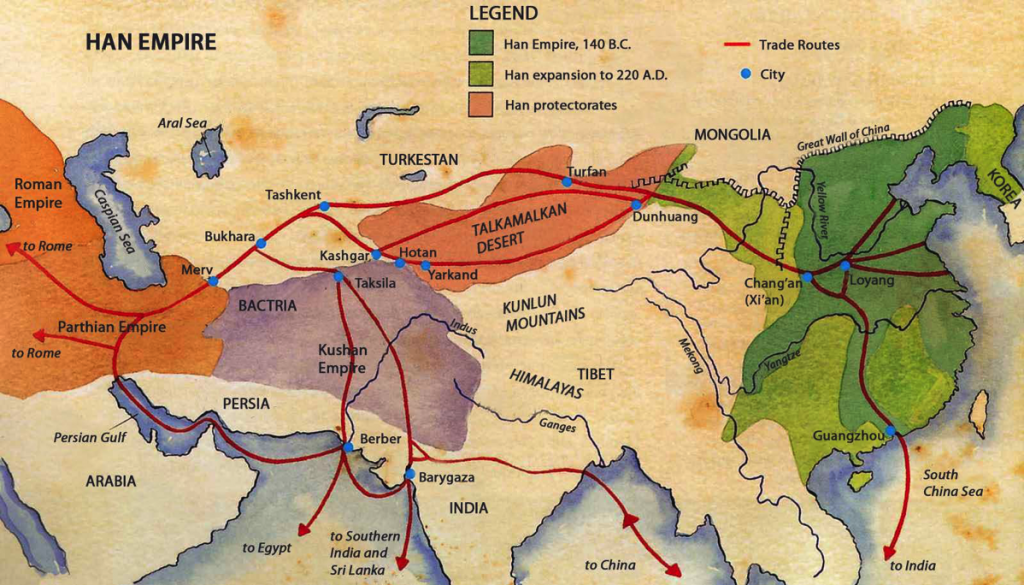

Silk was so valuable that traders came from all over Europe, Indonesia, and Africa to exchange goods such as horses, wool, gold, silver (to the east) and return to the west with jade and porcelain, salt, and silk. At certain periods, it was used as a form of currency at the imperial court of China.

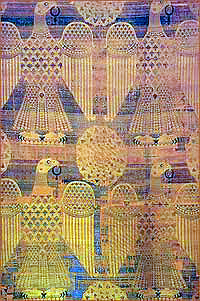

The Legend of Leizu and the Origins of Luxurious Chinese Silk

In an early form of trade-secret theft, traders for the Byzantine emporers were able to spirit silk worms and workers into Constantinople by the 5th century C.E. Court workshops produced their own stylized silks, under monopoly by the emperors. Much of this locally-produced silk was reserved for diplomatic gifts. Certain colors, such as the murex purples valued from ancient Rome, were held for the sole use of the royal family.

http://altmarius.ning.com/profiles/blogs/byzantine-silk-smuggling-and-espionage-in-the-6th-century-ce

Silk production was recognized as a lucrative addition to government incomes. Consequently, workshops and the skilled workers to run them were hired away from cities with established silk-producing factories repeatedly throughout the middle ages.

The muslim conquerors of the middle east established silk workshops in north Africa, Spain, and Sicily.

By 1204 the city of Lucca set up workshops with weavers escaping the recently-sacked city of Constantinople.

From there the cities of Genoa, Florence, and Venice established major silk-weaving businesses by the 14th century. By the 16th century, France had encouraged silk weaving centers in Lyon and Tours. In the 17th century, the English weaving center at Spitalfields absorbed silk technicians on the run from the religious persecution in France.

Linen is also ancient, and was heavily until the industrial revolution. No one knows how people figured out that if the stem were wet, the fibers inside it could be spun and woven.

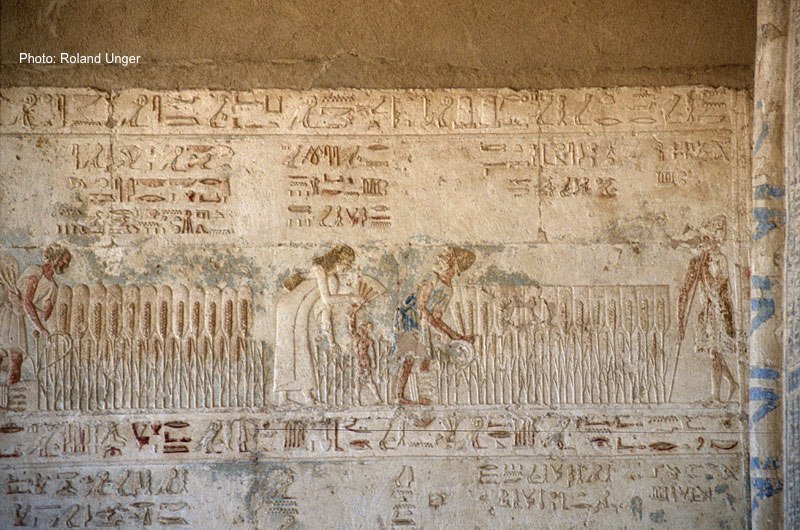

Woven linen has been found in Turkey, c. 7000 B.C.E. The world’s oldest remaining garment is also made of linen, c. 5000 B.C.E. in Egypt. This garment, currently in the Petrie Museum of Archaeology, University College, London, would have been likely been knee length originally. Its careful pleating and specifically V-neck suggest an aristocratic garment worn in a socially complex, wealthy society.

Ancient Egyptians wore mostly linen, woven into squares and carefully pleated and belted around the body. Egyptian mummies were also wrapped in long narrow yardages of linen.

By the time Middle Ages (roughly 400 C.E.-1500 C.E.) most European clothing consisted of a linen undershirt under outer layers of (usually) wool. Linen is sturdy and held up to frequent washing, as well as being cool in the summer and keeping body oils off the harder-to-clean outer garments.

The oldest cotton find is from the Neolithic find at Mehrgarh c. 7000 B.C.E. (now in Pakistan). More recent finds from Peru, c. 4000 B.C.E. show the oldest-known use of indigo as a dyestuff. The color and cloth of your blue jeans goes back a looooonnng way! Other species were cultivated in Egypt by 1600 B.C.E.

Four different strains of the cotton plant (Gossypium sp.), domesticated separately in different areas of the world. Strains of the plant included Meso-American (Gossypiam hirsutum) and South American (Gossypiam barbadense) versions; the Indus Valley (of India and Pakistan) variant (Gossypiam arboreum) became the dominant old-world strain of the plant, which spread to Africa, Asia, Greece, Iran, and Iraq. The Arabian/Syrian strain (Gossypiam herbaceum L.) also spread to Africa and still grows wild there. G. hirsutum has taken over in popularity and is the strain most cultivated today.

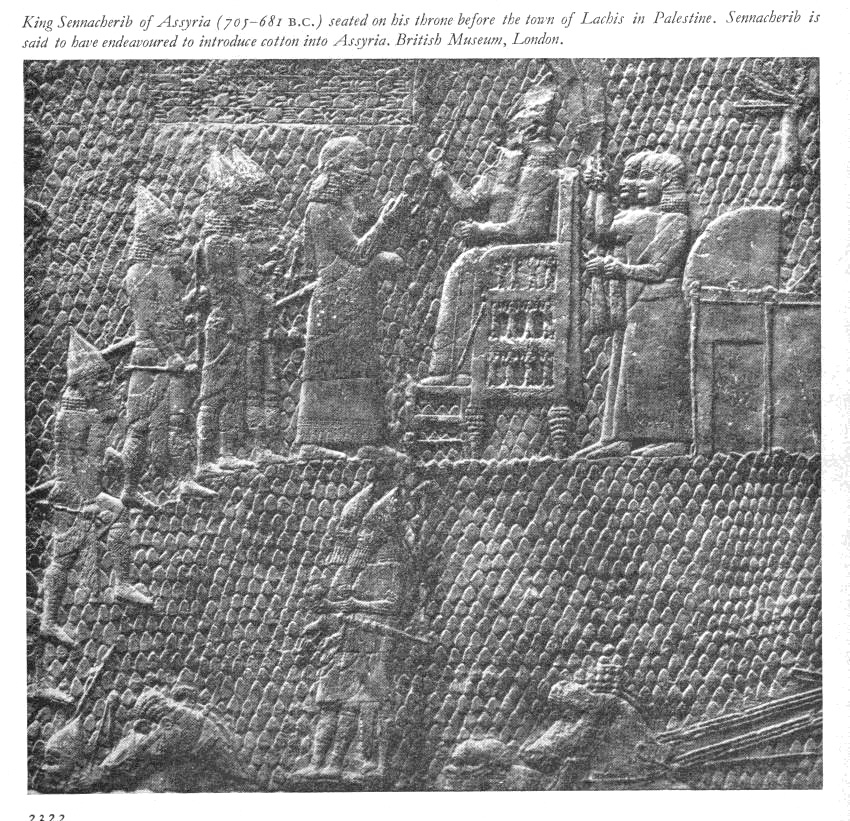

Cotton production and importation is mentioned in historic sources as diverse as early Sanskrit writings, Herodotus (c. 484-425 B.C.E.), and the Christian Bible.

The Domestication History of Cotton (Gossypium)

http://www.elizabethancostume.net/cibas/ciba64.html

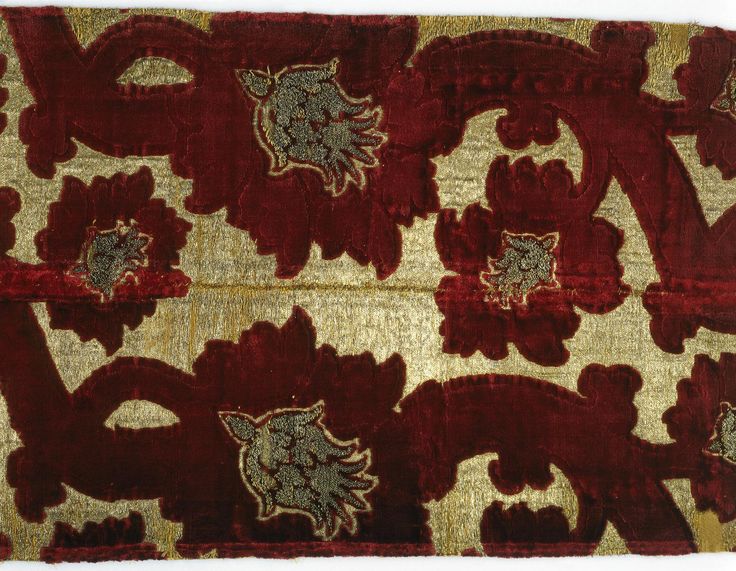

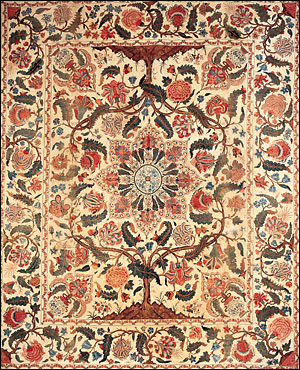

The Mughal (1526-1857 C.E.) empire in India encouraged cotton fiber and cloth production, partly as a response to expanding demand for colorful printed textiles in Europe and England. These household textiles grew popular as Portugese traders imported them in the 16th century. By the late 1500s, the leafy motifs printed along the Coromandel coast, called palampores, became major export goods for the Dutch. The British East India Company claimed their monopoly on Indian goods mid-18th century (c. 1757-1773), and the mania for these goods drove fashion and trade for a century more.

The craze for exotic Indian-style prints, colors, and woven patterns continued throughout the 19th century with the popularity of the paisley shawl (a wool story, not a cotton one). The popularity of Indian cotton prints led British manufacturers to create their own locally produced cotton goods. Technological advances such as the spinning jenny, the cotton gin, steam powered looms, and new forms of fabric printing allowed the British to take the lead in cotton weaving and finishing in western Europe for the rest of the 19th century.

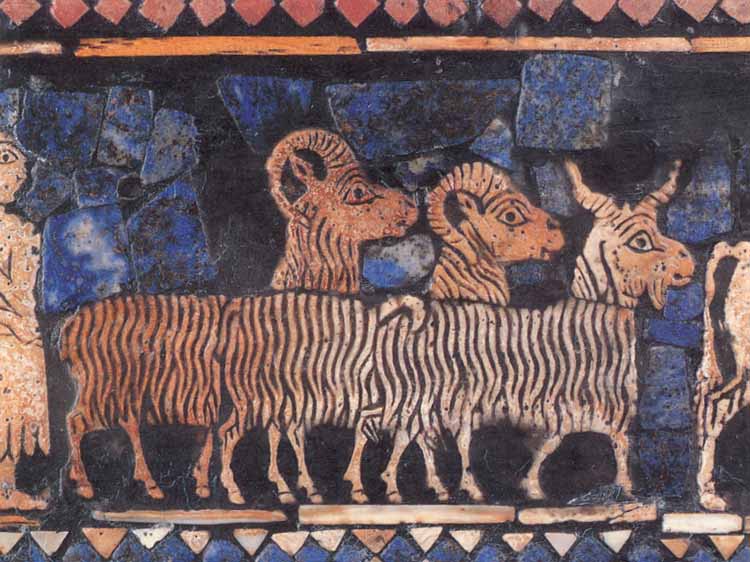

Wool is last of the four big fibers most used in fabric and clothing. Like silk, wool is a by-product of an animal’s life cycle. However, the domestic history of sheep’s wool is complicated by the fact that sheep were originally raised for their meat. Zooarchaeologists have found evidence at the site Asikli Hoyuk in Turkey that suggests that sheep were domesticated there about 8000 B.C.E.

Other evidence for wool production comes from the excavations at Ur, c. 2400-2000 B.C.E.

Evidence for sheep’s wool goes back to roughly c. 2700 B.C.E. in the Minoan culture and closer to c. 3000 B.C.E. in what is now Israel.

These are not the only natural fibers people use for cloth or clothing. Here is a listing of many more: Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles