By Karen Abington (Class of 2018)

It should come as no surprise to our alums that the watchword of this year’s Paris Seminar was – drum roll please – creativity. In discussing fashion, and especially French fashion, we would be remiss if we didn’t touch upon the creative process, and I imagine that this subject was a main focus of the seminars of years past. What was different this year, however, was the way in which this all-important subject was approached and – shall we say – deconstructed.

The centerpiece of this year’s Paris seminar was a film project, in which students from Paris, Hong Kong, and New York collaborated in the development, filming, editing, and presentation of a short documentary on the creative process of four Paris-based designers: Garance Broca, Jérôme Dreyfuss, Anne Valérie Hash, and Gustavo Lins.

This exercise was preceded by the screening of the documentary film Dreamers, which was shown at the 2012 Venice Biennale, and follows the creative process and personal story of 11 film directors and screenwriters, including Michel Gondry, Akiva Goldsman, James Gray, and Guillermo Ariaga. Director Noëlle Deschamps was kind enough to present her film and to assist as one of several filmmaking coaches throughout the seminar.

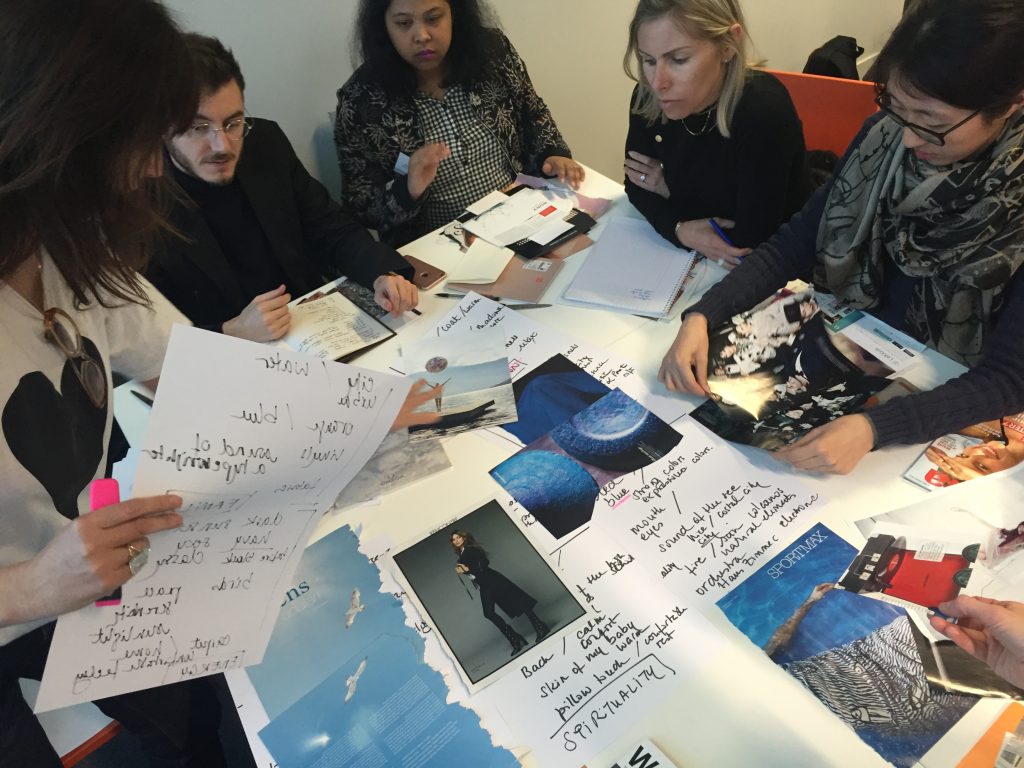

Our viewing of the film set the stage for what was to follow, as we broke up into our first meetings and started to explore our own creative styles and individual aesthetic proclivities in the context of our groups. To help us get to know each other, IFM GFM Director Véronique Schilling was prescient enough to organize a “five senses workshop” through faculty member and aesthetic specialist Jayne Curé. As a part of this workshop, we were asked to clear our heads and make a list of things or experiences that were important to us in the context of the five senses, freely associating between sight, smell, taste, touch, and sound. We then shared our individual aesthetic impressions among our groups to determine common themes. Everyone in my group, for example, touched upon the theme of the sky in one way or another, and so images of the sky became an important element of our short film.

Meanwhile, as we got to know each other and discussed potential angles and editorial points of view, each designer was kind enough to speak to the entire class about their work as well as their creative process and personal journey. In this way, students were able to get a sense of each designer’s unique character, which would later be on display in our short films.

First up was Jérôme Dreyfuss, of the eponymous handbag collection. Jérôme let his instantly lovable personality and sense of humor shine through. To set the stage, he recounted how he decided at age 12 that he would be a fashion designer after watching an interview of French chanteur Serge Gainsbourg, who said that he became a musician in order to seduce women. I guess Jérôme began to think about strategy at a young age: realizing that he couldn’t sing, he decided then and there that becoming a fashion designer might be the next best way to appeal to the fairer sex. Despite such humor and good cheer, it was clear that Jérôme is motivated by a sincere desire to help people. He is inspired by real women, and their real, everyday needs. One of the short films showed how Jérôme – who rides his scooter across Paris to work every day – is perpetually on the verge of an accident because he is constantly turning around to watch women as they pass. He is interested in what they wear and how they conduct themselves, but most importantly he wants to know how they carry their lives around Paris in their handbags. He is constantly tinkering with his designs, so as to make them more intuitive, more practical, and more useful to real women. This concern shines through in the finished product – Jérôme’s bags are light, versatile, beautifully made, practical, and above all, effortlessly elegant.

Second in the lineup was Garance Broca – designer of the knitwear brand Monsieur Lacenaire – who was accompanied by co-owner, brand manager, and husband, Benoist Husson. Monsieur Lacenaire is an extremely playful, humorous, and creative menswear line, whose designs are restricted only by the technical limits of the knitwear medium itself. Garance is so passionate about her craft that she studied and learned Italian so that she could communicate with the knitwear artisans and technicians in Italy, where much of her line is produced. Such seriousness and dedication has served her well. Throughout her presentation, she shared prototypes, stitch patterns, and yarn samples in different fibers and gauges so that we got a real sense of the complex art of knitwear design. Garance also has a playful side, however. The theme of her presentation was the process of ‘creative ping pong,’ whereby she is able to build and expand upon her ideas by constantly bouncing them off her husband and business partner Benoist. One of our documentary films thus focused on the dialectic between Garance and Benoist, both as a way to illustrate Garance’s creative process as well as show the playful characteristics of Monsieur Lacenaire himself.

Our third designer – Brazilian native Gustavo Lins – represented an interesting contrast to the careful planning required by the knitwear collections of Monsieur Lacenaire. Formally trained as an architect and bringing an undeniable structuralism to his craft, Gustavo Lins has worked for years in high fashion and has come to embody the spirit of a true couturier. He doesn’t read fashion magazines or follow the latest trends when thinking about his next collection. He goes straight to the mannequin and begins to drape and physically construct his garments, at times allowing his initial intentions to be influenced by the spontaneous emergence of an unexpected drape or silhouette. Gustavo turned out to be a touchingly open and sincere person. While he was busily constructing a beautiful garment before our eyes, he candidly and unselfconsciously shared details and memories from his personal life, thus allowing us insight to the person he has become today. Many in the audience were visibly touched by his openness. The filmmakers dedicated to Gustavo were able to tap into and expand upon this theme in their films, showing how Gustavo had emerged from personal and professional tragedy to become the fearless individual he is – a person who is capable of uniting people through his force of character.

Finally, Anne Valérie Hash gave a highly original presentation which was a fitting conclusion to our foray into the personal creative process. A classically trained dressmaker and couturier, native Parisienne Anne Valérie gave a lecture on the themes of construction and deconstruction, in which she disassembled a pair of men’s trousers in order to reconstruct a dress. Deconstruction – whether it be of a garment, of a motivation, or of a memory – is an important part of her creative process. Anne Valérie’s previous collections have included items of personal significance gifted to her by friends – Alber Elbaz’ sky blue pajamas, for example, or Tilda Swinton’s much loved Vivienne Westwood t-shirt. Such items are taken apart in order to build something new, personal, and original. In this way, beloved possessions are given new life. As a part of her presentation, each of us were asked to think about what we would most like to deconstruct – whether it be a garment, a memory, a photograph, or a book – and what we would hope to learn as a result. This exercise helped us to understand our deep motivations, much as Anne Valérie herself was able to gain insight to her own creative process in an interview captured on film by our students. As a Jewish women, she was recounting the Jewish tradition of the cutting of garments to signify mourning over the death of a loved one. As she was saying this, she realized that this tradition was reflected in her own work. Cutting – and deconstruction – is for Anne Valérie a way to pay homage to the events – both sorrowful and joyful – in each of our lives.

When Noëlle Deschamps was describing the inspiration for her film Dreamers, she recounted how her goal – to document the creative process of her favorite filmmakers – was initially met with skepticism and bemusement. How can you make a film about creation itself? Her detractors worried that it was simply too esoteric and abstract a subject to be successfully portrayed on film. She ploughed ahead however – she had faith in her vision – and eventually all of the pieces fell into place and she was able to make her dream come to life.

On second thought, is this really an accurate description of what happened? To say that the pieces simply fell into place does the creative process a disservice by making it appear effortless. In point of fact, Ms. Deschamps must have fought very hard for her film. Through hard work, willpower, and the courage of her conviction, she was able to overcome the objections of her detractors.

Each of us has an innate creative ability, and the 2017 Paris Seminar was very successful in demonstrating the process of creation. Despite this, the most important thing that I learned from Ms. Deschamps – and from each of the designers who shared their lives with us – was that creativity is not enough, in and of itself. It takes courage, tenacity, and discipline to bring your dreams to fruition. For me, this seminar was more than anything a manifestation of the human spirit and a glorious celebration of our artistic differences. Like our four disparate designers, each of us is formed by our own unique experiences, and each of us is therefore inimitable. Perhaps it is not exactly topical, but in reflecting on this experience, I am reminded of a passage which struck me when I first read it, and which has stayed with me ever since. In describing his theory of evolution in The Origin of the Species, Charles Darwin said: “there is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” Let us therefore always celebrate our differences – these “endless forms most beautiful” – and the indomitable spirit which make us who we are – each of us unique, each of us irreplaceable.

****

Below, “It’s Playtime” is the short video my group created to showcase the creative perspective and process of Parisian knitwear brand Monsieur Lacenaire. Among the eight different team videos created, this was the final jury selection for “Best Director.”