Godey’s Lady’s Book, published between 1830 and 1898, established the foundation for contemporary American fashion magazines. The longest running ongoing publication to address interests of women in the nineteenth century, Godey’s Lady’s Book included fashion coverage, domestic matters such as housekeeping and cooking, and fiction and poetry written by American authors. The magazine’s longtime editor, Sarah Josepha Hale, is credited with creating the “Thanksgiving” holiday and using Godey’s to promote its adoption nationally.

The illustrations included in each issue promoted fashions of the time and instituted a monthly frequency for disseminating information, creating a desire and a sense of urgency in the reader to purchase, reproduce, and interpret fashion. This post offers a history of the fashion plates as they developed with Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Sarah Josepha (Buell) Hale was born in Newport, New Hampshire, on October 24, 1788. Although she did not acquire a formal higher education, Hale studied beside her brother and later with her husband, David Hale, whom she married at the age of twenty-five in 1813. In 1822, David Hale died of pneumonia, and in order to support her five children Sarah Hale found work as a seamstress. She wrote a book of poetry in 1823, garnering the attention of the publisher Louis Antoine Godey.

In January 1828, Hale moved to Boston to edit American Ladies’ Magazine and Literary Gazette, a periodical focusing on subjects specific to the American public such as fashion, education, social reform, and American literature. In 1834 the title of the magazine changed to American Ladies’ Magazine (colloquially referred to as Ladies’ Magazine) where Hale remained editor until 1836.

Hale is credited with influencing President Abraham Lincoln to issue a “Thanksgiving Day Proclamation” in 1863, although Thanksgiving was not recognized as a legal holiday until 1941.

Louis A. Godey, born in New York on June 6, 1804, relocated to Philadelphia in 1828 and founded Lady’s Book in 1830. In 1836, Godey acquired Ladies’ Magazine, and Hale moved to Philadelphia to edit Lady’s Book in 1837, remaining in this role until her retirement in 1877.

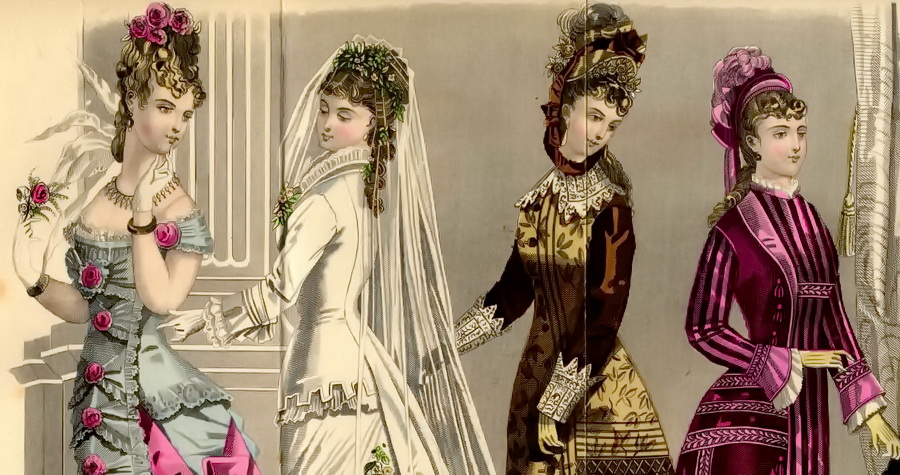

During the first thirty years of Godey’s Lady’s Book, one colored fashion plate was included in each issue. By 1840, the majority of contributors to Godey’s Lady’s Book were female. Women hand-tinted the steel and copper fashion engravings, and “at one point 150 ladies did the work, using another color for a dress when the first ran out, and by the practice causing periodic consternation on the part of the readers” (Kunciov 1971). Addressing the variations of color “when the supply of one color ran out, [and] the artist blithely used another,” Godey stated in the May 1839 issue, “we now color our plates to different patterns so that two persons in a place may compare their fashions, and adapt those colors that they suppose may be the most suitable to their figures and complexions…” (Finley 1931).

Steel engravings, called “embellishments,” were included in each issue of Godey’s, and Godey placed the responsibility of interpreting the fashions on the reader. Promoting fashion in Godey’s during the 1830s did not necessarily support the pious, domestic, separate women’s domain which Hale held in high esteem, and Hale had “early misgivings about the subject of fashion and the use of illustrations as it countered the virtues of the women’s sphere – purity and lack of regard for frivolity. It was with some reluctance that Hale published fashion plates” (Lewis 1996).

The fashion illustrations used in first decades of Godey’s were imported from France, and Godey’s also used plates from Townsend’s Selection of Parisian Costumes (published in London from 1823 until 1888), although many plates in Townsend’s originally appeared in Le Journal des Dames de des Modes, published in Paris between 1797-1839.

Therefore, many of the fashion illustrations published in Godey’s were not original, and “shortly after she took over as editor, Mrs. Hale began to hire local artists to redraw for Godey’s the fashions that appeared in foreign publications. As a result, a single illustration may be a composite of sources as well as of dates, some as much as year apart” (Blum 1985). By 1850, metal plates were imported from France, such as those created for Le Moniteur de la Mode and frequently reprinted in Graham’s Magazine.

As fashions became outdated, text on the plate was erased and then it was re-used. This practice improved the quality and quantity of the plates printed in Godey’s. During several months in 1850, the following text appears on plates: “Godey’s Imported Fashion Plates” (April), “Purity Plate: improvement on the French” (August), “Godey’s Americanized Fashion Plates”– engraved by J.I. Pease” (December).

The same green and black dress depicted in a fashion plate printed in the April 1866 issue of Godey’s also appears in the French publication Cendrillon circa 1865.

The European gowns represented in Godey’s color fashion plates were not necessarily practical for the average nineteenth-century American woman, and:

…one wonders if Mrs. Hale or anyone on her staff really ever came face to face with many of the fashions they featured in the colored plates. The captions were often vague as to the fabrics used in the dresses, and at times the colors as described in the text do not correspond with those in the hand-painted plates. In spite of these shortcomings and the impracticality of some of the high styles shown, these plates did supply the stuff of dreams for many an American woman (Lewis 1996).

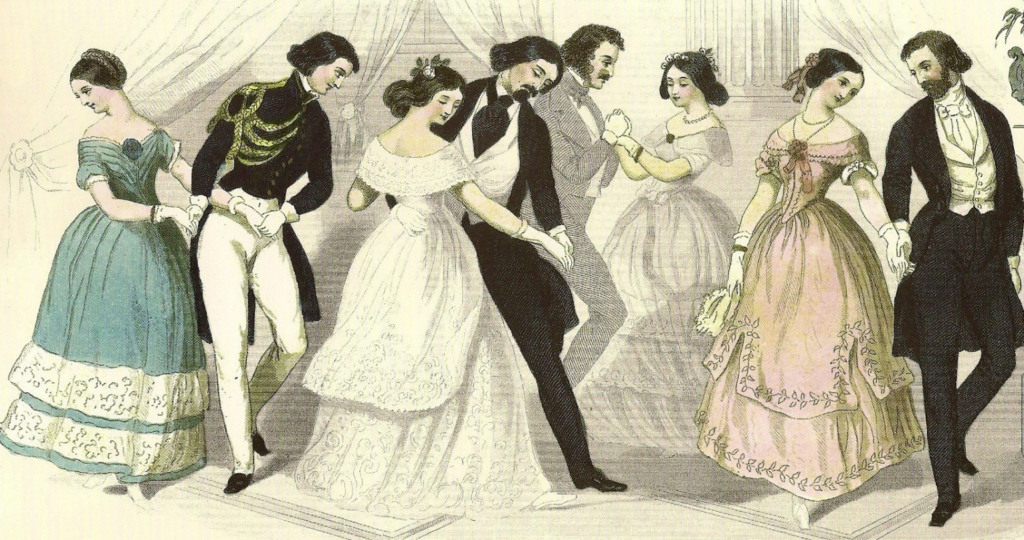

Fashion plate from Godey’s Lady’s Book,

May 1864

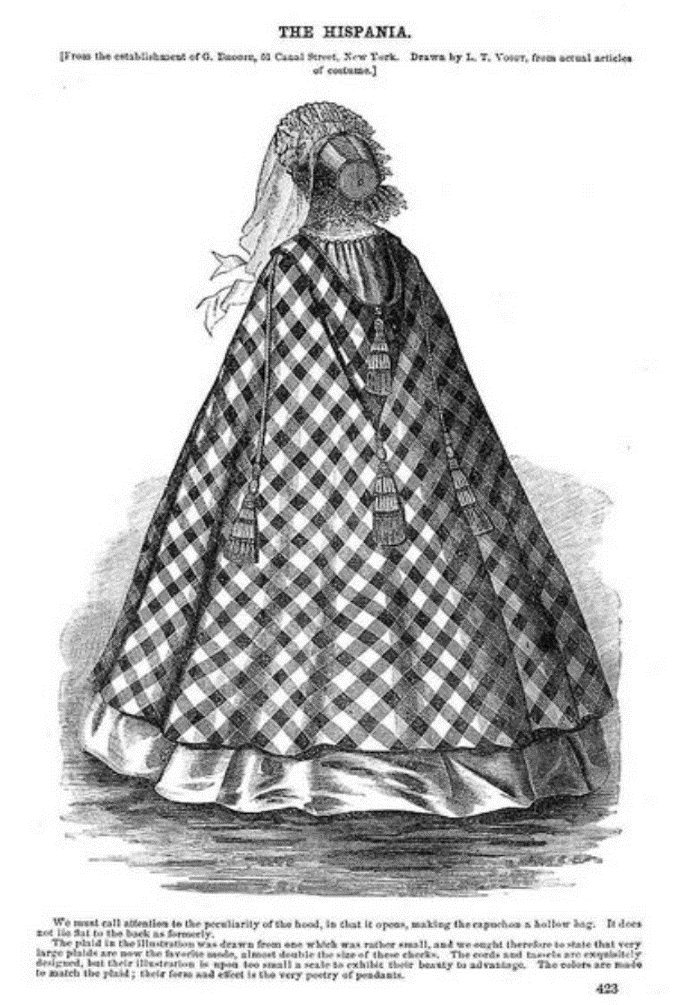

Godey’s began to include black-and-white drawings of simplified versions of European clothes, usually day dresses that could be recreated by American dressmakers. Many of the plates during the 1850s and 1860s state “from the establishment of G. Brodie, 51 Canal Street, New York. Drawn by L. T. Voight, from actual articles of costume,” providing the reader with the name and address of the New York fashion house should she wish to purchase the French and English-inspired dresses.

Capewell & Kimmel were prolific engravers based in New York, and their work is frequently published in Godey’s during the 1850s and early 1860s. The caption under one fashion plate of a cape from 1864 states: “the plaid in the illustration was drawn from one which was rather small … very large plaids are now the favorite mode, almost double the size of these checks. The cords and tassels are exquisitely designed, but the illustration is upon too small a scale to exhibit their beauty to advantage, the colors are made to match the plaid; their form and effect the very poetry of pendants.” The text, likely added after the image, explains how the engraving does not depict the most up-to-date fashion.

The scope of Godey’s Lady’s Book encompassed more than fashion, including essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Horace Greely, criticism by Edgar Allan Poe, poetry by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Charles Leland, and fiction by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Herman Melville, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hale introduced an “Editor’s Table” column in 1836, encouraging letters to the editor. This invitation to create dialogue was novel and relatively informal for the time, and “assumed equal and personal relationship between editor and reader” (Lewis 1996). Hale credited all of her writers with bylines, and promoted the role of women as authors.

The burgeoning middle-class during the nineteenth century provided a new audience for Godey’s—urban, middle-class women with time to read, and rural women, too, reading for domestic advice. Godey’s was popular in both northern and southern states, although the Civil War marked the decline of Godey’s due to its avoidance of addressing the war. Hale’s circumvention of controversy and politics eliminated any direct mention of the suffrage movement or the Civil War from the pages of Godey’s. Rather, she focused on “women’s interests” such as dress, homemaking, motherhood, education, and professional career development. Hale strongly advocated for women’s higher education and facilitated the founding of Vassar College in 1861.

In 1849, Godey’s had 40,000 subscribers, and by 1851, Godey’s had a circulation of 63,000, double the number of any contemporaneous title. By the Civil War in 1861, the circulation reached 150,000. The price for an annual subscription was $3.00, considered expensive for the time and equivalent to $85.00 in 2018.

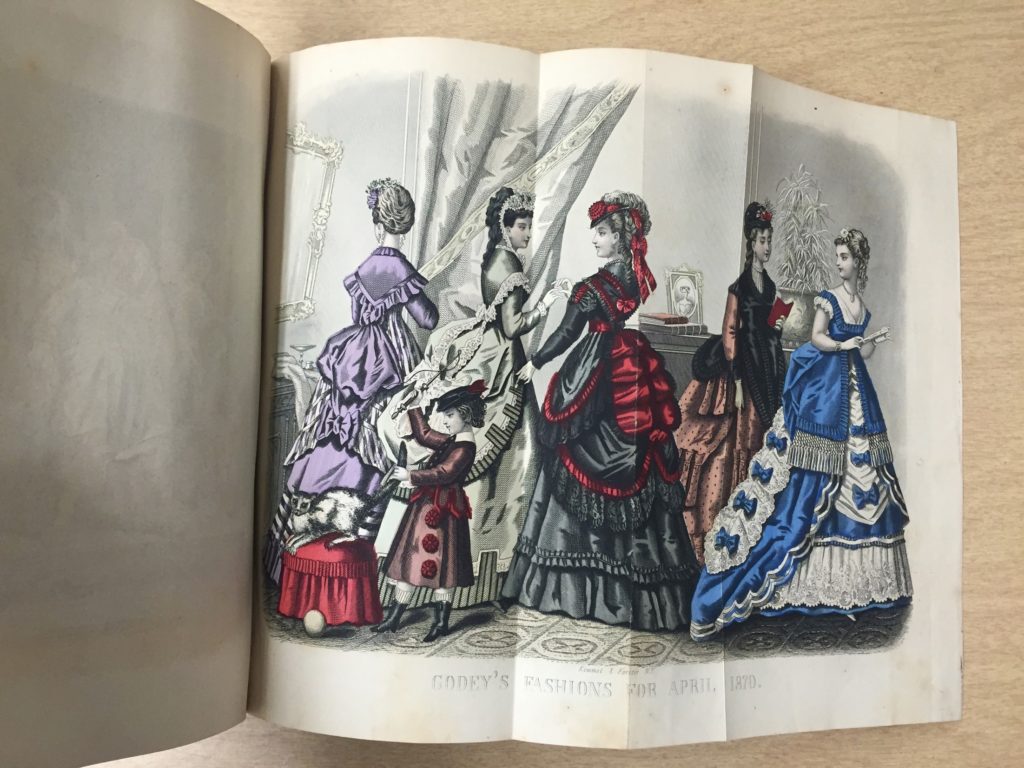

By 1849, Godey’s printed twenty color plates, and published 1,000 steel plates by June 1870. Initially, Godey’s Lady’s Book was six and a half inches wide and ten inches high, royal octavo size with two columns of print per page. Two volumes with six issues were published annually, and the early issues had continuous pagination; page numbers were not restarted at each month. In 1872, a table of contents was introduced after the cover page, and each issue began separate pagination at this time.

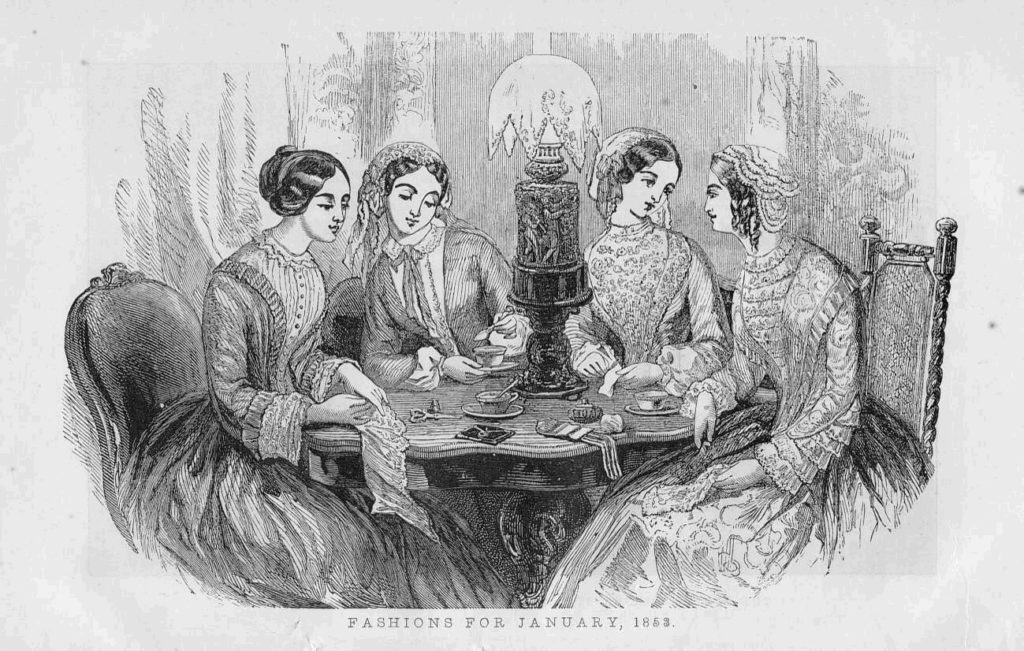

A full-page illustrative plate was bound inside each front cover with regular monthly features included at the back of each issue. In 1847, mezzotints, a new type of black and white illustration, were added, and by the 1850s more text became devoted to fashion coverage with the “Fashions” feature introduced in 1853.

In 1861, double-sized plates were produced which had to be folded in order to fit within the octavo volume. These extension sheets usually featured five figures dressed in current, fashionable styles, posed somewhat artificially against interior and outdoor scenes appropriate for each season.

The figures in the extension sheets were always arranged in various angles – from the front, the side, the back, and three-quarter view—illustrating clothing from multiple vantage points and in different postures of movement. The colored pages were often torn from the pages and used for home decoration. Extension sheets were phased out in 1877 when plates were printed on two adjacent pages.

In 1880, half-tone electrotypes replaced the historic fashion pates, and by 1883 the fashion plates are no longer hand-tinted (Tortota 1973). During the later years of Godey’s, illustrations were interspersed throughout the volumes and placed within the text copy.

In addition to “Fashions,” regular monthly features included: “Editor’s Table,” published monthly since 1836, “Godey’s Arm Chair,” “Novelties,” including information about fashion and household items, and “Receipts,” introduced in 1857 covering recipes, health, grooming, and household issues. Advertising was incorporated by 1847. Descriptions of color and black and white plates with summaries of fashion trends in Europe, New York, and Philadelphia were printed in the back of each issue, and a column called “Chitchat” provided additional fashion news. Issues contained original sheet music “composed for the piano for Godey’s Lady’s Book,” serialized fiction, a “Works” department covering traveling costume, accessories, hairstyles, and patterns such as those created by Madame Demorest. A “Juvenile” department included hymns and poems for children, and residences “designed expressly for ‘Godey’s Lady’s Book’” were offered the option to purchase floor plans for $15.00 to build the house in the illustration.

The impact of Godey’s throughout its decades of publication during the nineteenth century established fashion as an important topic in women’s magazines. Sarah J. Hale was not the fashion editor of Godey’s, although fashion was the only editorial feature she did not manage. Louis Godey had to remind readers of this information in his “Godey’s Arm Chair” section: “Mrs. Hale is not the Fashion Editress, Will our subscribers please remember that? Address you letters to Fashion Editress, care of Godey’s Lady’s Book, Philadelphia, Pa” (1864). However, Hale’s influence on fashion is evident throughout the magazine. Fashion contributed to women’s social and career development, and readers tended to value and follow Hale’s advice, wishing to dress appropriately for higher education and the workplace.

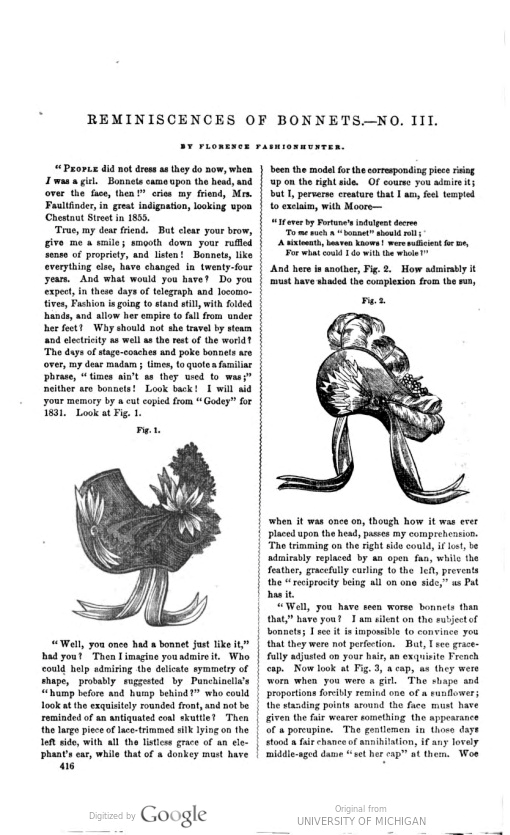

The rapidly changing nature of fashion is explicitly addressed in an article titled “Reminiscences of Bonnets,” written by “Florence Fashionhunter” in May 1856: “Do you expect in these days of telegraph and locomotive, Fashion is going to stand still, with folded hands, and allow her empire to fall from under her feet? Why should not she travel by steam and electricity as well as the rest of the world?”

The writer critiques three reprinted drawings of bonnets originally published by Godey’s in 1831, comparing one to “all the listless grace of an elephant’s ear, while that of a donkey must have been the model for the corresponding piece rising up on the right side,”and another’s “shape and proportions forcibly remind one of a sunflower; the standing points around the face must have given the fair wearer something the appearance of a porcupine. The gentlemen in those days stood a fair chance of annihilation, if any lovely middle-aged dame ‘set her cap’ at them.” The article’s ridicule of twenty-four year old bonnet styles highlighted in Godey’s early issues addresses women’s trends with humor and criticism, challenging stagnation and reluctance to move forward with the current of fashion.

Both Hale and Godey retired in 1877, and Hale’s published goodbye states, “and now, having reached my ninetieth year, I must bid farewell to my countrywomen…” In 1877 Godey’s was sold, and new editors took over on January 1, 1878. Hale died on March 30, 1879 in Philadelphia.

The publication frequency of Godey’s steadily disseminated information, exposing women to regular news. The inclusion of fashion plates further created a sense of sartorial urgency in the reader to adopt new styles and anticipate those for the future. The magazine “became the vehicle to showcase apparel and promote the latest fashionable style. As a result, Godey’s audience followed the magazine’s advice and standards toward fashionable dress” (Lewis 1996). Godey’s impacted the rate of fashion change by sharing new styles, including dressmakers’ names and addresses, mail-order services, and depicting American recreations of current dress. The apex of Godey’s Lady’s Book’s popularity in Antebellum America, a time of westward expansion, improved communication, industrial growth, and a new middle class, influenced women’s fashion journalism well into the twentieth century.

References

Aronson, Amy. “Everything Old Is New Again: How the ‘New’ User-Generated Women’s Magazine Takes Us Back to the Future.” American Journalism, 31, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 312-328. Accessed November 16, 2018.

Barker, Elizabeth E. “The Printed Image in the West: Mezzotint”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Accessed November 13, 2018. .http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mztn/hd_mztn.htm.

Blum, Stella, ed. Fashions and Costumes from Godey’s Lady’s Book. New York: Dover

Publications, 1985.

Brekke-Aloise, Linzy. “’A Very Pretty Business’ Fashion and Consumer Culture in Antebellum American Prints.” Winterthur Portfolio, vol 48, no 2/3: 191-212.

Finley, Ruth E. The Lady of Godey’s, Sarah Josepha Hale. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1931.

Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine. Philadelphia: L.A. Godey, [1854-1882].

“Godey’s Lady’s Book.” Nest: A Magazine of Interiors, no. 21 (Summer 2003): insert 10- insert 42.

Godey’s Magazine [microform]. New York, [etc.] : The Godey Co.

Kunciov, Robert. Mr. Godey’s Ladies: Being a Mosaic of Fashions & Fancies. Princeton [N.J.] : Pyne Press, 1971.

The Lady’s Book. Philadelphia: L.A. Godey & Co.

Lewis, Mary Jane. “Godey’s Lady’s Book: Contributions to the Promotion and Development of the American Fashion Magazine in Nineteenth-Century America.” PhD. diss., New York University, 1996.

Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906.

Patterson, Cynthia Lee. Art for the Middle Classes: America’s Illustrated Magazines of the 1840s. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010.

Tortora, Phyllis G. “The Evolution of the American Fashion Magazine as Exemplified in Selected Fashion Journals, 1830-1969.” PhD. diss., New York University, c1973.

Comments

One response to “Thanksgiving Special Magazine: Godey’s Lady’s Book”

Old fashioned more elegant and simple very nice