In the opening chapter of her book A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The Home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution, curator and scholar Joy Spanabel Emery cites the October 1916 issue of Designer magazine: “There is nothing so cheap & yet so valuable; so common & yet so little realized; so unappreciated & yet so beneficial as the paper dress pattern. Truly one of the great elemental inventions in the world’s history— the tissue of dreams.”

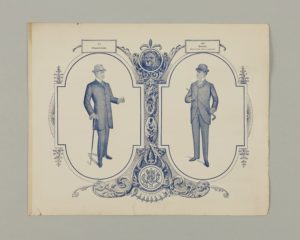

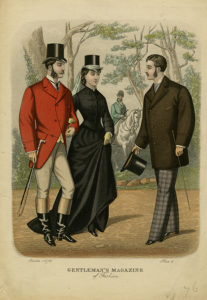

Far from only detailing womenswear and the history of commercial dress patterns, Emery’s book cracked open a wealth of information about many of the menswear publications we hold in FIT Special Collections & College Archives. We were delighted to learn more about our substantial holdings of menswear periodicals including Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion, Scott’s Mirror of Fashion and The Tailor & Cutter.

Established in 1828 by Louis Devere, Gentleman’s Magazine of Fashion was a trade publication which included drafts and patterns for tailors. During the 19th century, a marked shift took place in the dissemination of the techniques and tricks of the tailoring trade as information became increasingly available by way of printed publications. Prior to this time, tailors by and large received their education by way of apprenticeships, which often started at the tender age of eleven or twelve. In exchange for their labor, the mentors’ knowledge would be passed down to the apprentice who might launch a tailoring venture of their own after a decade plus of learning the trade. Often times this knowledge included copies of patterns which were treated as trade secrets, being handed down within a lineage of tailors, from one generation to the next. So valued were these proprietary paper patterns they were sometimes referred to as ‘gods.’

With the growth of the publishing industry during the 19th century, books and magazines became available to increasing numbers of individuals. From the technical to the promotional, fashion-related content became available to the middle classes for the first time in a way it never had been before. The market now expanded, many publishers searched for innovative ways to engage with tradespeople in particular. Once strictly protected by individual tailors, publications began publishing information about drafting systems as well as scaled down paper patterns and offering full-size paper patterns for sale. A curious business model developed; in order to promote one’s paper pattern business, many entrepreneurs launched fashion magazines, using them as platforms to advertise their wares. Oftentimes, these connections between the publication and the paper pattern enterprise are heavily obfuscated which was one of the most revelatory aspects of Emery’s book which unearths the connections between them, and and enduring a business model which was implemented for more than a century.

Launched in the 1870s, The American Tailor and Cutter was the promotional vehicle for John J. Mitchell’s paper pattern company which “offered to make patterns to the customer’s measurements, and supplied ready-made menswear patterns ‘cut from the finest manila paper… for FINE CUSTOM TRADE.’ ” A similar origin story for the company Butterick, which today is most associated with patterns for womenswear; in 1866 Ebenezer Butterick launched The Tailor’s Review to promote his earliest offerings— tissue paper patterns for boys and menswear. Their womenswear patterns were offered by way of a sister fashion publication, The Delineator, from 1873 onwards.

While FIT Special Collections and College Archives does not hold an inventory of the paper patterns themselves — our holdings were donated to the Commercial Pattern Archive at the University of Rhode Island in 2016 — our periodical holdings evidence the rich connections between fashion magazines, the commercial pattern industry and the tailoring trade.