While sorting though a recent donation, a small collection of exquisitely detailed sketches by one Fira Benenson came to perk my curiosity. Her name was unfamiliar to me, and as someone who spends a great deal of time immersed in fashion history ephemera, I know that often this means a fascinating discovery is at-hand.

While sorting though a recent donation, a small collection of exquisitely detailed sketches by one Fira Benenson came to perk my curiosity. Her name was unfamiliar to me, and as someone who spends a great deal of time immersed in fashion history ephemera, I know that often this means a fascinating discovery is at-hand.

I was not wrong.

Pouring through both the Women’s Wear Daily and New York Times historical databases, I was delighted to learn that Benenson was one of the America’s leading tastemakers from the late 1920s into the 1960s. She was born in Baku, Russia in 1898 into an affluent family. Her father, Grigori, made his fortune in the oil industry and after founding banks in both St. Petersburg and London, he became banker to the last tsar of Russia, Nicholas II. The Benenson family fled to London during the Bolshevik revolution of 1917/1918, landing in London for a period of about three years before immigrating to New York City in 1921. There her father—who was characterized by press at the time as an “international capitalist”—put down roots as controlling partner/president of the New York Dock Company as well as owner of several large downtown office buildings.

As a young twenty-something who had grown up attending Paris couture shows several times a year with her mother, the New York fashion market seemed a natural fit for Fira, who opened a dress shop on Madison Avenue as both a source of personal income and also to provide work for fellow Russian émigrés. As the head of Verben, Fira traveled to and from Paris selecting couture models from top designers including Vionnet, Chanel, Paquin, Molyneux and Augustabernard, which were then retailed through her store. She developed a reputation for her impeccable taste, favoring elegant lines and restraint over the exuberant embellishment which found favor with many other American buyers.

In 1934, she was tapped by Bonwit Teller to head their Salon de Couture. Adored by her staff—although reputed to be ruthlessly frank with clients—”Miss B” took nearly the entire staff of Verben with her to Bonwit Teller, from seamstresses to sales staff. Her operations at the department store functioned much as they had previously; she served as directrice, traveling to Paris at least four times a year to select the couture models which were offered in her Salon at Bonwit. The backing of one of the top American department stores now meant she enjoyed elite status in terms of bargaining power. She took advantage of this by negotiating exclusive imports, meaning that any couture look sold in her Salon could only be had at Bonwit Teller; it would not be licensed to other department stores or high-end dress shops. This fact, paired with supreme customer service (not only did Fira buy models with specific clients in mind, clients would arrive to appointments to find all necessities to complete the outfit—lingerie, hats, gloves, shoes and the like—already pulled from other sections of the store) made a her powerful figure in the fashion industry, both in America and abroad. The fashion press sought out her opinion on matters of la mode so frequently that it is confounding that she has largely been forgotten today.

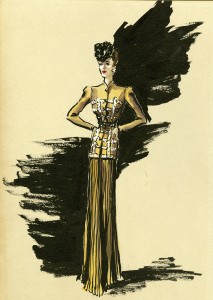

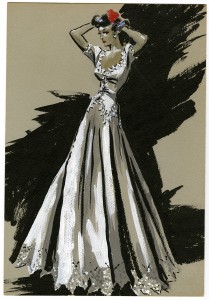

The spotlight would shine brighter and brighter on Fira beginning in 1939. With war in Europe looming on the horizon, Benenson quietly assumed a new mantle: fashion designer. Until this point, she had been a stylist and buyer, but not the creator of original fashions. Critics lauded her very first collection: “Everyone had counted on her good taste and knowledge of fine workmanship to produce an adequate collection of clothes. But no one took for granted what did happen: that Fira Benenson should produce original clothes as well as any top-flight Paris designer!” Inspiration from her Eastern European roots seeped into the collection by way of Russian-inspired embroidery and skirt silhouettes based on traditional Polish aprons. The sketches in our collection, which all date to 1940, build a case that she also turned to museums for inspiration. The sketch at left below bears a hand-written notation on the back “Bonwit Teller/Designed by Fira Benenson/Goya Spanish jacket” while the one at far right is labeled “adapted from museum source.” This museum source may very well be the collection of the Museum of Costume Art, which was founded in 1937 as a resource for costume, fashion and textile designers to study garments and textiles of the past. In 1946, the Museum of Costume Art merged with The Metropolitan Museum of Art to become The Costume Institute, which was once home to this selection of sketches.

That Benenson’s signature style emerged to be one of restrained elegance was likely no surprise to her former clients, but perhaps the delicacy of her touch was; she quickly became known for exceptionally fine details—painstaking shirring, impossibly tiny tucks and gossamer lace-covered evening gowns. She gravitated toward svelte silhouettes and a willowy look she created by dropping waistlines 1 1/2″ from the norm. Two examples of the “picture necklines” which were part of her design lexicon for many years can be seen above at center and right.

In 1947, Benenson decided to venture out on her own, leaving Bonwit Teller in 1948 after developing a private wholesale line on the side. Her first venture into ready-to-wear was said to have a “made-to-order feeling” and to be practically “indistinguishable from her couture collections, except that it is made in sizes.” Prices began at $110 in currency of the day, which is just over $1,000 adjusted for inflation today, and for a time her ready-to-wear designs were offered exclusively Lord & Taylor. Many of these pieces were designed with women 40 and over in mind, as Fira herself was approaching 50.

A truly dynamic woman of her era, Benenson spoke seven languages fluently and her interests included world politics and throwing dinner parties with her husband, the Polish nobleman Count Janusz Ilinski.

5 responses to “From Russia with Love: Fira Benenson”

Hortense Odlum, Bonwit’s first female President, recognized that the store needed a couture salon as other retailers such as Saks already had one; however, she also wanted to meet the needs of domestic high end customers as war loomed in Europe. In corresponding via telegram with Gladys Tilden, Bonwit Teller’s trend reporter stationed in Paris, Benenson signed all of her correspondence as the Countess Illinska. There are a few surviving examples of Beneson’s design work in the MET collection.

Thank you Michael! Nice to know that someone else has interest in Benenson. I’m going to email you privately to discuss more!

Hi April, looking forward to speaking about this.

What a thrill for you (and the rest of us), April! You have the best job in the world. And you can be sure I’ll be looking into this Russia born designer who eventually specialized in older women.

What a thrill for you (and the rest of us), April! You have the best job in the world. And you can be sure I’ll be looking into this Russia born designer who eventually specialized in older women.

https://www.suambalaj.com/